Concord, Massachusetts is very pretty. Charles Ives’s “Concord” Piano Sonata is not.

Every movement of the piece, completed in 1915 as an ode to the spirit of Transcendentalism, grows either quaintly or grotesquely from the first four notes—the “fate” motive—of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

In the first movement, “Emerson,” the theme’s recurring interval of a third is diffused through dreamily dissonant cluster chords, noisy aleatoric runs across three staves, Brahmsian farces of arpeggio-melody work, and a slogging chorale, among other delights.

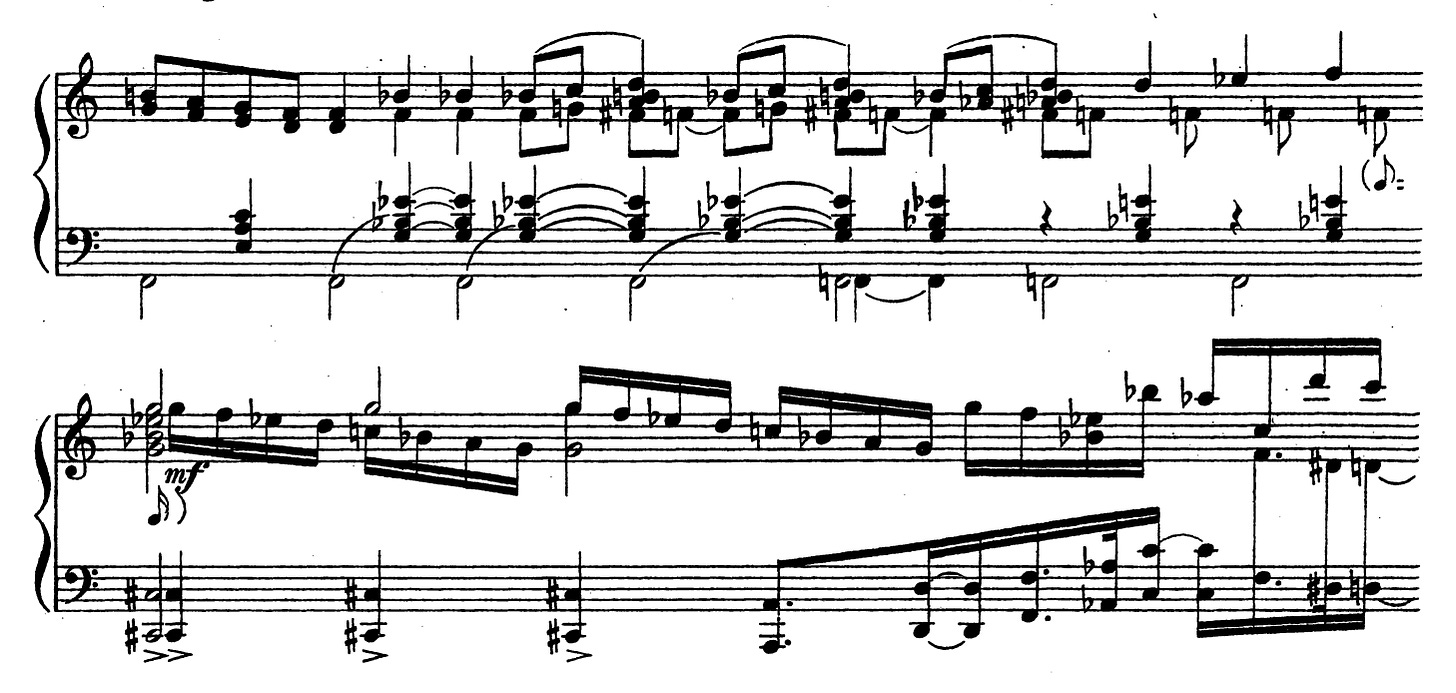

The motive is rendered just about indiscernible for most of the second movement, “Hawthorne,” a crazed fantasia that in one section requires the pianist to use a board to depress a range of keys in the upper register, creating a far-off atmosphere that wouldn’t again be realized until George Crumb’s Makrokosmos sixty years later. It quotes Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cakewalk” before bursting into an old American anthem, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.” It also quotes “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” a popular song in the Union during the Civil War.

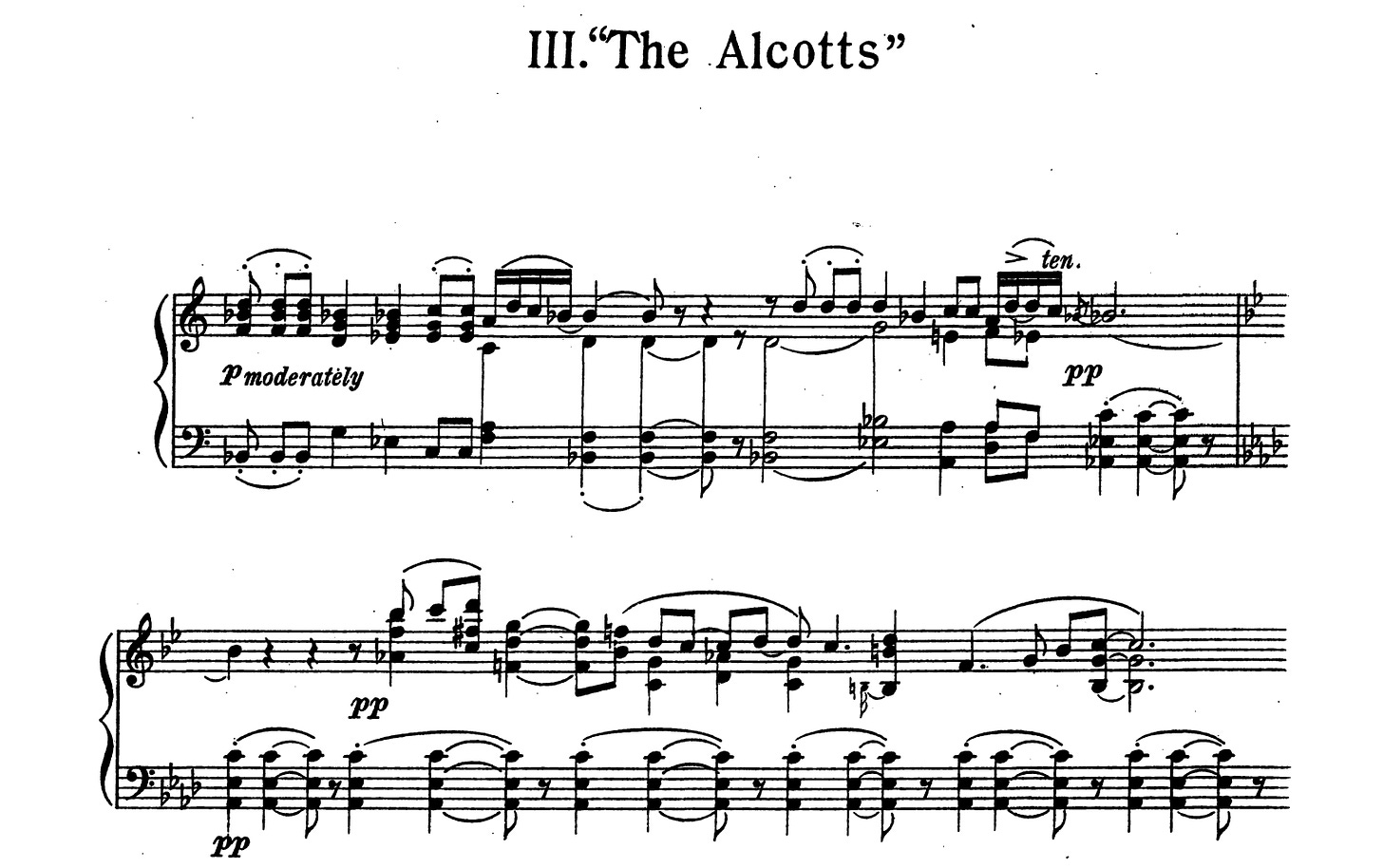

Beethoven’s theme appears like a provincial traveller at the beginning of the third movement, “The Alcotts.” It’s as though we’ve been traveling through the woods and have come upon the four notes at rest by Walden Pond. But it soon metamorphoses into a gorgeous pseudo-rag. So much of the movement is bathed in elegant Wagnerian tonicizations—brief shifts to a different key—(the unexpected Bb-over-Ab is especially sigh-inducing) that you almost forget that Ives was composing in the twentieth century, while at the same time you almost remember that he was born well before it.

The last movement, “Thoreau,” is more sober than the others, although it stops and starts, and when it starts again it really starts, often growing louder and faster before abruptly halting. It winds down with a steady repeated rhythm of three slowly ascending octaves, funeral-like, and yet appropriate for the earthy loner of the movement’s title. The fate motive arises intermittently, peaceful, and the sonata finishes with one more statement of a third—an A-major one, far away from the ostensible starting key of Bb major.

The experience of listening to the “Concord” Sonata is one of stylistic and temporal disorientation. One moment, we’re soaked in an acid of dissonance that anticipates1 the most radical experiments of the European, and later American, avant-garde; the next, we’re lulled into a Shaker-like calm by the simplicity of familiar harmonies. Here, we’re jolted awake by a patriotic anthem, brimming with the youthful energy of a budding republic; there, we’re buried in thorny contrapuntal mimicry that sounds like it was composed by a tone-deaf Bach. The piece sounds literally time-less, in the sense that is seems to exist outside the realm of a specific historical period. And yet, because of the amount of quotations from American hymns and canonical European masterworks, it is teaming with history.

You’d think a piece composed over a hundred years ago would sound old. And yet the “Concord” Sonata sounds new. Like most of Ives’s music, which frequently employs extensive quotation, this piece did not just anticipate the 20th century avant-garde; it is still avant-garde, even in 2024, one-hundred-and-fifty years after the composer’s birth.

I don’t think the same can be said about Schoenberg, Ives’s closest contemporary analogue. Schoenberg’s atonal and twelve-tone music, the latter of which was first introduced in his Suite for Piano (1923), lacks humor and takes itself too seriously. It never pokes fun at itself or its predecessors because Schoenberg saw his method as the natural next step in the grand German tradition of Beethoven. Serious music for a serious mission. But whenever Ives quotes anything, it’s always absurd, and thus a little funny, because it’s rendered phantasmagoric by the surrounding dissonance. Schoenberg’s seriousness now seems archaic, while Ives’s sarcasm has lasted.

Today, Ives’s evergreen radicalism is apparent in the fact that there are so few celebrations this year for his sesquicentennial. My editor at The Brooklyn Rail, George Grella, recently wrote about this.

On the one hand, I understand why George is infuriated that more of an effort hasn’t been made by American orchestras to celebrate Ives and make him a more central presence, if not the central presence, in the canon of touchstone American composers. Having attended a recent concert by the Momenta Quartet for their own Ives celebration series, I can even say concert curators are really missing out on some opportunities to create fascinating programs, not only promoting Ives’s music, but other little-known American composers. Or, as George suggests, programming both Ives’s and Brahms’s second symphonies in one concert. My heart races at the thought.

On the other hand, this reticence to embrace Ives means that his music is doing exactly what it’s supposed to. Even though Ives didn’t intend his music to be unpalatable for a wide audience (indeed, he repeatedly said he composed for the common man), a niche listenership is the outcome that the music itself actively fosters. And that’s a good thing. Because it proves the lasting revolutionary potential of Ives’s music.

Despite his seemingly old-fashioned nature and his post-War longing for a more innocent America, Charles Ives was a dialectical composer. His work interrogates the past, elides the distinction between it and the present, and forms the foundation for a revolutionary theory of music history.2 Charles Ives should thus never be celebrated by powerful classical music institutions.

Two Fridays ago, days before the composer’s birthday, Sony Classical reissued a 5-CD box set, originally released in 1974, dedicated to Ives. Recordings of the composer’s works, tapes of Ives playing and singing, and a slew of recollections by people who knew him, all recorded by the oral historian Vivian Perlis, grace the collection. In one of Perlis’s interviews, Bigelow Ives, the composer’s nephew, reminisces about his uncle. He tells the story of an evening walk they once took together.

Ives was an old man and left his residence at 164 East 74th St. in Manhattan to visit the family house in Danbury, Connecticut, his hometown. After he wandered around the home, fondly remembering scenes from his childhood, he took Bigelow to the Civil War monument in the town square. When they arrived, Ives noticed that the elms which used to be there were gone. New, strange buildings had popped up all around. Ives walked a little then leaned on a box by the curb. He buried his head in his hands and moaned. He told Bigelow he wanted to go back to the house. “You can’t recall the past,” he said, sorry that he went out in the first place. “From that,” Bigelow said, “I had an inkling of how deep his love was for a bygone way of life that he had apparently nurtured ever since having left Danbury as a boy.”

Anecdotes like this abound in these oral histories. From Ives shaking his fist at noisy airplanes overhead; to Elliott Carter’s story of going to hear the Boston Symphony Orchestra with him, after which his disparaged Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring as “simple-minded;” to his never reading newspapers or listening to the radio, Ives resented the modern world. Ives especially resented America’s involvement in the World Wars. He grew up in an optimistic atmosphere of post-Civil War patriotism. His childhood, replete with Fourth of July parades, baseball, and a musician father who instructed him to sing hymns in one key while accompanying himself on the piano in another, was idyllic. But as great of an actuary as Ives was, there was no Mutual Life Insurance plan that could compensate for the America he had lost.

So, Ives was nostalgic. And, on its face, so is his music. But while Ives himself constantly looked to the past and lamented its loss, his music itself looked to the past and ended up looking to the future. And I don’t mean in the way people usually talk about it—in terms of those musical techniques I pointed out above like dissonance or cluster chords or randomness. I’m talking about the latent political meaning in his use of quotations. Here, we need some theory to help us understand.

In The Dialectical Imagination, Martin Jay’s seminal 1973 history of the Frankfurt School—the World War II-era group of mostly German-Jewish expats, like Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, notable for merging the thought of Freud and Marx and advocating praxis, applying theory to the real world—the author lays out the two strands of aesthetic criticism traditionally pursued by Marxist thinkers. One, derived from Lenin, valued only works that have a definite partisan bent (i.e. socialist realism). The other, derived from Engels, valued works not based on their creator’s political intentions but by the actual social significance of the works themselves. As Jay summarizes, “The objective social content of a work, Engels maintained, might well be contrary to the avowed desires of the artist and might express more than his class origins.” This is, of course, Frederic Jameson’s “political unconscious.”

If we are to follow the second line of thinking, as most reasonable Marxist critics have done, how can we possibly locate, on the one hand, Ives’s “avowed desires” (i.e. his political beliefs), and, on the other hand, the “objective social content” (i.e. what it says about the world) in the “Concord” Sonata, a piece of music with no words? The answer lies in the quotations. But we have to be dialectical about it. After all, Ives was.

I’ve always struggled to define what it means to be “dialectical.” I eventually learned that that’s the whole point. You’re not supposed to be able to define it. The Marxism of the Frankfurt School—which you often hear referred to as dialectical materialism—is all about “nonidentity,” the impossibility of an identifiable human nature or any identifiable, “transcendental” truth (in the sense of transcending time, manifesting in every historical period). No absolutes. The only constant is what the political scientist Shlomo Avineri called “Anthropogenesis,” our ability to create ourselves anew. (In other words, we’re back at Heraclitus’s “the only constant is change”). To look at something dialectically is to be, in Jay’s words, “a gadly of other systems,” to analyze something through “contrapuntal interaction.” There is no dialectical manifesto. You can’t even make the word into an “ism.” It “negates”—antagonizes, questions, interrogates—everything, and yet it stands for nothing. It’s in this sense that Ives’s music is “negative.”

The most helpful way to think about being dialectical that I’ve found is a statement by Adorno, the music guy of the Frankfurt School.3 “A true dialectics,” Adorno wrote in 1956, was “the attempt to see the new in the old instead of simply the old in the new.” This was Schoenberg’s achievement: Employing a new harmonic language to compose in traditional musical forms. And in fact, in 1969, the philosopher Georg Picht called Adorno’s philosophy just as “atonal” as the music he had absorbed from Schoenberg. Had Picht, a German, known about Ives and understood him properly, he might have amended this characterization to include the Danbury denizen.

When Ives quotes something, he excavates potential out of it that its creator could not see. When he quotes Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony—a fixture of orchestral programs and wealthy classical music institutions everywhere—he miniaturizes its importance and intensity. He hides its main theme in weeds of other notes. But he also maximizes it. He blows up the theme to absurdly huge proportions at the end of “The Alcotts” by overdoing it with keyboard-spanning C-major chords. Beethoven would have hated this, or at least would have totally failed to comprehend it.

By quoting Beethoven in an almost messy, vulgar, or even “disrespectful” way, Ives antagonizes the canon and the very idea of canonicity. And he disproves the supposed ahistoricism of music—the notion that music exists in the time it was made and cannot be acted up by later history. The avant-garde (and historically-informed musical practice) now accepts and embraces this way of looking at history and at the ownership of music, but Ives’s music was saying it in 1915 and earlier (!). Ives shows the temporal continuity of music: no discrete musical work is untouchable or immutable. Any music can be used and crafted in ways other than the composer intended. He tears down the divine “aura” (as Walter Benjamin called that spirit of an art work that can’t be replicated by mechanical reproduction) that accompanies the great works. He finds the new in the old by using the old in the new.

He does the same thing with American patriotic music by exposing its latent, violent ideology. The most obvious and heavy-handed example of this is Ives’s performance (the third take) of his song, “They Are There!”, featured on the fantastic album Ives Plays Ives. Here are some lyrics, which you really must listen to to understand the anger Ives infuses them with:

Then it's build a people's world nation Hooray Ev'ry honest country free to live its own native life. They will stand for the right, but if it comes to might, They are there, they are there, they are there. Then the people, not just politicians will rule their own lands and lives. Then you'll hear the whole universe shouting the battle cry of Freedom. Tenting on a new camp ground.

The predominant quotation in this song, is, once again, “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” The way Ives treats it doesn’t just say “when World War II is over we’ll finally be free.” It seems to say, due to the angry language and tone of Ives’s performance, that the promises of this patriotic anthem were never true in the first place. Elsewhere in the song he sings, “Most wars are made by small stupid selfish bossing groups, while the people have no say.” He seems to be expressing an eternal condition of America, and saying that it is in fact a contradiction.

In the “Concord” Sonata, we don’t need the words of “The Battle Cry of Freedom” to understand how the music exposes the hypocrisy of the anthem’s message. As seen in the excerpt above, the melody rises in the right hand before cascading in repeated figures of sixteenth notes. The melody never resolves. The music itself expresses the failure of the message of the anthem and the incompleteness of the promise of freedom within it. The promise of freedom that Americans to this day repeat to the point of banality.

This is what the music says. Maybe Ives didn’t say it and maybe he didn’t think it. But when you quote European masterworks and patriotic anthems in a way that seems to destroy their institutional importance and their idealistic meaning, I think you have to conclude that the music is revolutionary. Revolutionary in the sense of “negating” the past—the powerful past: Beethoven, America.

In his book Prisms, Adorno wrote about what characterized a successful work of art:

A successful work, according to immanent criticism [the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School], is not one which resolves objective contradictions in a spurious harmony, but one which expresses the idea of harmony negatively by embodying the contradictions, pure and uncompromised, in its innermost structure."

I can’t think of a better description of Ives’s music.

Later on in life, Adorno’s admiration for Schoenberg’s music waned. The main reason was because his twelve-tone method caught on in the academy, especially as European refugee composers came to New York. Serialism because the way to compose if you studied music at Columbia, for example (see Milton Babbitt). If all budding composers had to compose like Schoenberg to be considered worth their salt, then the “negative,” anti-establishment quality of Schoenberg’s music was dead. His method had become the establishment. “To be true to Schoenberg,” Adorno concluded, “is to warn against all twelve-tone schools.”

I think we can say a similar thing about Ives. To be true to Ives is to warn against acceptance of his style. I’m glad his music still makes us uncomfortable. I’m glad that powerful musical institutions are slow to accept him into their regular programming. Let him stay on the outside. And let’s not praise him for his antagonistic music. Critical Theory, the Frankfurt School, Hegelian Marxist— it was all unknown to him. He couldn’t have been following a “dialectical theory of composition” and he never would even if he knew about it. But let’s study him. Let’s describe what his music does: it is praxis. Critical Theory before Critical Theory.

One last word from Adorno. In the preface to his Negative Dialectics, he writes that “dialectics is the ontology of the wrong state of things. The right state of things would be free of it: neither a system nor a contradiction.” In other words, if things weren’t so fucked up, we wouldn’t have to question everything all the time.

Things are fucked up right now. So let’s look to Ives’s music to help us question fascism, idolatry, and patriotism, and not elevate him to any status.

So even though Concord, Massachusetts is very pretty. Remember that Ives is not. And let’s not prettify him by making his music a fixture at Carnegie Hall or anywhere else that represents power in music.

With Ives, it’s often difficult to decide when to use “anticipate” and when to use “influence.” Since so much of his music went unperformed and unpublished in his lifetime, keeping it from affecting contemporary musical discourse, I tend to think “anticipate” is appropriate, although once his music became widely known it was of course influential.

If you’d like to witness in real time how I came up with this idea, listen to the latest episode of The Best Is Noise. I did an all-Ives program, which broadcasted live on October 21, 2024 on Radio Free Brooklyn. (Ignore the first few minutes, which, due to a technical snafu, was the beginning of a previous episode on Bruckner.)

If you want to get into Adorno’s music writing, you might first start with Edward Said, who saw himself as Adorno’s successor. Both are crucial reading. I know of no other writers who were just as musical as they were literate. Start with Said’s Musical Elaborations and then go to his Late Style (keep his Music at the Limits, a compilation of mostly concerts reviews, by your toilet). Start with Adorno’s essay on Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and then read the rest of Night Music (especially his essay on Schubert) and then his Philosophy of New Music. He shits on jazz, which obviously sucks, but it’s worth remembering that the jazz he was exposed to was Tin Pan Alley jazz. I don’t believe he ever heard guys like Ornette Coleman or Coltrane. So keep that in mind.