All The Bones Had Names

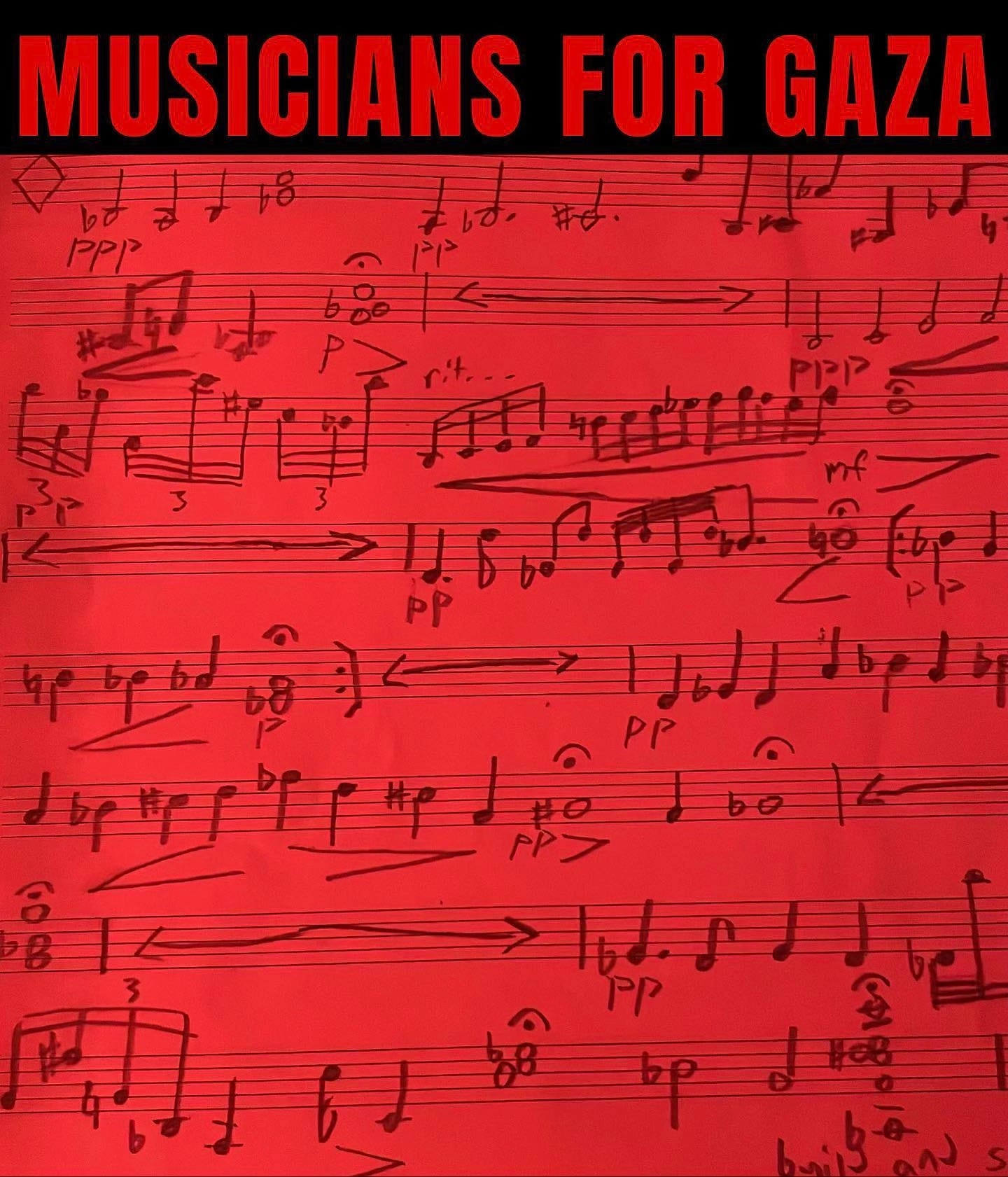

Musicians make some noise for Gaza in benefit concert at Fifteenth Street Quaker Meeting House.

“It’s hard to believe it if you haven’t seen it for yourself. Still, you have to try really hard not to see what’s happening now.” -Benjamin Moser, “Israel, Zionism, Apartheid”

“Freedom is a very good horse to ride, but to ride somewhere.” -Matthew Arnold

Saturday evening, over the course of three hours, musicians young and old came together at the Fifteenth Street Quaker Meeting House near Union Square to play and raise money for both the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund and the American Friends Service Committee’s (AFSC) emergency relief fund.

Lawyer, community organizer, and AFSC New York Healing Justice Program Director King Downing called the event a “Ceasefire Musical Benefit.” The Committee’s U.S. Peacebuilding Director Lewis Webb, Jr. informed the audience that one of AFSC’s on-the-ground team members in Gaza had emailed him during the performance after a period of radio silence, asking him to thank the audience for their charity, which went to medical supplies for hospitals in the besieged city.

Gabe Boyarin, who is a student at Berklee College of Music and plays lead guitar for Anteater Eater, an excellent Victoria-based band, organized and emceed. David Watson, highland bagpiper and founder of the new Striped Light concert series, presided from the wings.

While last Monday’s book launch at Roulette was a who’s who of one generation of experimental NYC musicians (1980s), Saturday evening was a cross-section of a different generation. A younger, weirder, darker, less funny, more serious, perhaps more hopeless generation. And who could blame them?

Yet the reverence with which the musicians—over twenty-five of them—approached their craft made up for the dark cloud which hovered over the room, imbuing it with a concentration that allowed for deep listening and open-eyed dreaming.

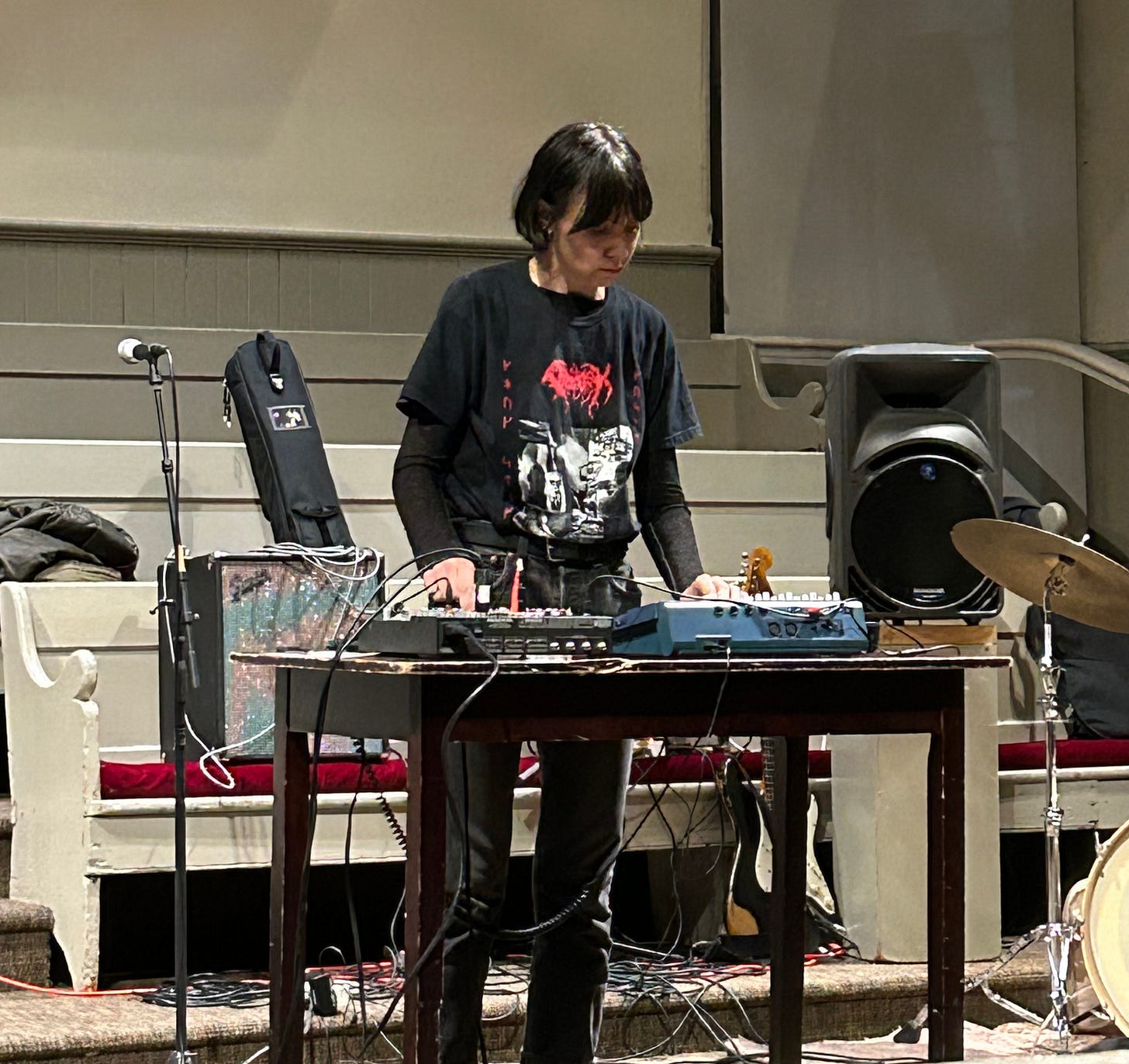

That reverence began with Rachelle Rahmé, a Lebanese-American poet and MFA candidate at Brown, who turned knobs on a synth, melding faint guitar picking with organ timbres to create a quiet, gloomy, continuous sound cloth. A couple times, she popped out a cassette tape and replaced it. A pre-recorded woman’s voice recited a poetic monologue, at one point saying something like, “When I repeat, ‘I know,’ I am really saying, ‘I am.’” This was one of Rahmé’s first forays into electronic music (she appears on To Whom I’ve Never Met and Only Imagined, a 2021 album by Snake Union), but I think she has a nice road ahead of her in this field, so profound, solemn, and sensitive, though not atypical, was her performance.

Brandon Lopez followed with a defiant, vicious, epic upright bass set. In what sounded like one long improvisation, Lopez stared at the audience as he strummed on the neck and under the bridge like a mad man, making the strings hit against the instrument so hard that it sounded like a bass drum. All the while, he hummed, unmiked. His hum sometimes swelled into a muted cry, although he kept his mouth shut the whole time. His playing turned angry, as he formed his right hand into a finger gun, which he slapped against the neck. The last bit was governed by a march-like V-I (if I recall) cadential pulse that Lopez interrupted with spontaneous bursts of ripping into the strings with his whole hand. He ended by drumming the body of the instrument with both hands. It was electrifying.

The volume rocketed up to eleven as David Watson (bagpipes), John King (electric guitar), and Gelsey Bell (vocals) followed with another improvisation. Moving from piercing loud (not sure how I feel about bagpipes indoors) to cool quiet—King, solo at one point, had some beautiful melodic phrases—the performance was exemplary of Watson’s grating style, but no less astounding. Unsettling, yes, but I sense that’s the intended effect. Bell intoned ritualistic, Amazonian yawps.

Anthony Coleman then ushered in some tranquility with a solo piano piece that I’ll call a “text to music” composition. “Mapped,” in Coleman’s words, onto Mahmoud Darwish’s poem, “Those Who Pass Between Fleeting Words,” the music pairs each note or chord with a syllable, resulting in a rhythm which was sometimes predictable, according to the poem, and other times unnatural. Coleman encouraged the audience to follow along on their phones. I was lost at first, but by the second stanza, I got what he was doing. I mouthed the words to myself, surprised at how well he mimicked and modified the meaning of the poem, superimposing his own wordless narrative onto the violent and mournful text.

“Let’s see what music can do,” Huda Asfour said before she conducted the newly-formed (summer 2023) Brooklyn Improv Orchestra. Asfour led the ensemble in a group improvisation that was free-ranging, formless, and framed by a set of big unison thuds. I wasn’t impressed, despite the fact that it included great musicians on some great instruments, like oud and santur. The balance between the instruments stayed the same most of the time and it was hard to tell whether the musicians were playing off of each other, or just watching Asfour for direction. Such is the trouble with “conducted improvisation,” I guess. But I suspect this is because the group’s chemistry has yet to form. If sufficient funding and participation allow the ensemble to flourish, I hope we’ll hear more from them.

But I was blown away by Roy Nathanson’s set with Alber Baseel (drums) and Julian Soto, who sang Nathanson’s, “All The Bones Had Names.” The song appears on his October album, 82 Days, which was inspired by the nearly three months he spent during the pandemic convening jam sessions outside his Flatbush home. With soul fit for a Marvin Gaye track, Soto sang, “All the bones had names / no one claimed,” which Nathanson repeated in plain speak. “The bones were stars that had yet / to be discovered,” Soto continued. Backed with a bass drone and gently erratic percussion, the gospel-infused song was the most sincere and moving set of the night.

Amir ElSaffar’s trumpet/santur songs mesmerized me. He first played a composition that grew out of a recent improv. He called it, “The people of Gaza will be free.” Faint, long, swelling notes gave way to periodic fortepiano bursts from high note to low note. In this and the second song, “Weep, Weep, Weep, Oh, My Heart,” his multiphonics (several notes played at the same time on an instrument that usually produces only one note at a time) were astounding, sounding at one point like an amplified bass.

I didn’t stay for the last two sets simply because I was already exhausted from two and half hours of music. But it’s a shame I didn’t tough it out, because the final half hour was stacked: Gabe Boyarin, Anthony Coleman, Roy Nathanson, Marie Carroll, Beth Ann Jones, Marc Ribot, Shahzad Ismaily, Ches Smith (!).

Experimental musicians know better than anyone that to have freedom isn’t enough; you have to use that freedom. Anyone can bang on a can, scream into a microphone, or make deafening feedback with an amp and an electric guitar, but it’s what you achieve, or at least hope to achieve, which makes that freedom worth having. It’s who listens to you and who is inspired by you. Riding the horse of freedom, to use Matthew Arnold’s analogy, means using your freedom to make others free. Captives can’t free captives; only the free can do that. It’s only logical that Saturday evening’s musicians took this to heart and didn’t sit on their freedom horse.

What’s the point of having freedom if you don’t help others get free, anyway? Freedom isn’t selfish. If it were, well, that seems to me more like captivity.