Praeludium

These posts always consist of one long review or essay. Today, I’m trying my hand at sending out an actual newsletter.

Since the start of the year, stuff has been happening. The new music scene in New York City is booming. Last fall, I had the feeling that live music was back for real. It still feels like people are buzzing to get out. With that shift, I assumed—as anyone who thinks that as time goes on, the arts progress, does—something had changed. I was on the lookout for trends.

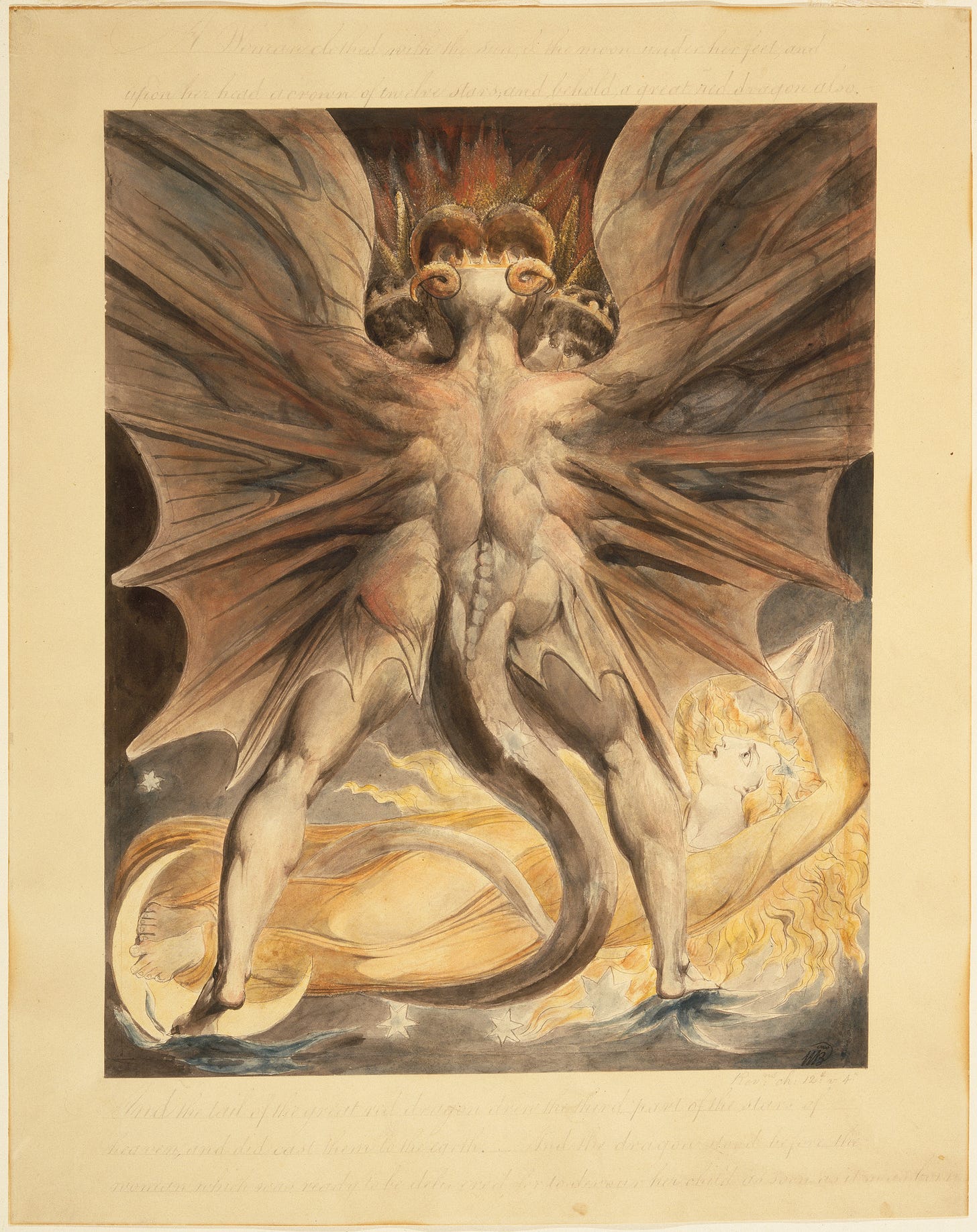

Since I’m a research historian by trade, I was wondering what the pandemic had done to new classical/experimental/avant-garde music in this city. As any good cultural materialist knows, the arts respond to the culture; they are never outside of it. I read too much literary criticism about Romantic literature to not assume that cataclysmic events—the Black Death (Chaucer and Boccaccio), the Lisbon earthquake (Voltaire and Leibniz), the Industrial Revolution (the social art of Dickens, the spiritual art of Coleridge and Blake), the French Revolution (Beethoven)—catalyze philosophical and technical shifts in the arts.

COVID was, for all our denial and inability to process the whole thing, on par with these events. It was apocalyptic. And we Westerners love a good apocalypse. As M. H. Abrams, who taught Harold Bloom at Cornell, argues in Natural Supernaturalism, Romantic theory and literature—that of Wordsworth, especially—was based on the apocalypticism of Milton’s Paradise Lost, whose model was The Holy Scriptures, which ends in the Book of Revelation, detailing The Rapture. I don’t need to tell you that we’re still in that tradition today. Remember 2012?

But I don’t feel confident about settling on any one or two trends. That will have to happen in fifty years or so. What I do know is that the pandemic made everyone question everything. And post-pandemic performances have made me question what “live music” even is.

Live music, generally speaking, used to connote music performed in front of an audience, intended for a live audience. But during the pandemic, there were no audiences, which means composing with an audience in mind didn’t just seem like selling out or going commercial, as it has meant for generations of high-brow composers (Milton Babbitt), but was simply impractical. It would be fruitless, virtual audiences be damned. (It’s just NOT THE SAME, as any musician will tell you. If you want a better explanation than that, read my colleague Tyler Loveless on the phenomenology of remote learning.)

The improvised music that rules the New York new music scene right now may be in part due to that restriction. A lot of it, I feel, doesn’t take into consideration the audience at all. Often it seems like—sounds like—musicians are just playing for each other or rehearsing. It’s like the music wasn’t meant for an audience. And we, the audience who are actually there, are an intruder.

Make no mistake, that is a criticism. Improvised avant-garde music is not usually the kind of thing I really enjoy. So a lot of it is unpleasant for me. But that doesn’t mean I’m not interested in it immensely and think it should be covered. Plus, my taste is changing anyway, and as I explore the scene, interview musicians, and review concerts, my mind is opening. And that’s the experience I try to give to every reader and, as you’ll see below, listener, when I play, write, or speak about music.

So, my preliminary, overarching, generalizing judgement on the trend of avant-garde music in New York in fall/winter 2023: Music for musicians.

The Best Is Noise

Most exciting for me so far this year has been the stuff happening outside of Evenings With The Orchestra. I am beyond grateful for my faithful readers, free and paid, and I’m going to keep covering concerts here. But The Best Is Noise, my show on Radio Free Brooklyn, has been where I’ve found the most joy.

If you don’t know it, The Best Is Noise is a classical music show that I host live every Monday from 2PM to 3PM. I play music that doesn’t usually get played on classical stations. It’s rarely easy listening. It’s sometimes difficult listening. But my goal is to convince non-aficionados that it’s okay to listen to difficult, noisy, ugly stuff sometimes. You just have to know why it sounds that way. Then maybe you’ll like it.

For the past few months, I’ve tried to play some of the newest of the new music coming out, with a focus on New York artists, especially from Brooklyn. This year, I want to do more interviews.

Last Monday, I aired my interview with legendary pianist Ursula Oppens, whose eightieth birthday concert is happening on February 3 at Merkin Hall. The interview is now available on the show archive.

The Monday before that, I aired my interview with vocalist Shelley Hirsch, who has been a fixture in the Downtown Manhattan/Brooklyn experimental scene for over four decades.

Tomorrow, I’m having composer Theo Haber (whose December album The Man From There is wonderful) and Leonard Bopp, founder and artistic director of the young, budding Black Box Ensemble, on the show. We’ll talk about the ensemble’s debut Roulette performance from last night, Theo’s rubber chicken, and Brahms.

Some other episodes in the archive I’m proud of are my Best of Noise 2023 countdown, my interview with pianist Aaron Diehl, who spoke about his Grammy-nominated recording of Mary Lou Williams’s Zodiac Suite, and “Who’s Afraid of Arnold Schoenberg?”, my stab at rehabilitating the composer’s reputation in the hearts of non-specialist, lay listeners.

Writing Elsewhere

I’m also proud of the writing for publications I did last fall.

I am especially thankful to Village Voice editor Bob Baker for giving me the opportunity to interview and write about Julius Eastman’s brother, the jazz guitarist Gerry Eastman (“Gerry Eastman—Not Just His Brother’s Keeper”). I had been going to his jazz club, the Williamsburg Music Center, for a few years, and always wanted to do a piece on him. I thought he would reveal an essential angle to the music of Julius, which is in the midst of a huge revival. He delivered. I also thought Gerry should get his due, since no one had ever written in depth about him and his music. He is so important. Kyle Gann, writing for the Voice, was the first to announce Julius’s death, in 1990, so I thought this was a nice full-circle moment.

I’m also deeply grateful to Brooklyn Rail music editor George Grella for indulging my pitch to write about Ben Manley, a sound engineer, colleague of La Monte Young, and found-sound composer who has been a central figure in the Roulette and Roulette-adjacent crowd for decades. And yet, as far as I could tell, no one had written about him in depth either. I’m following up “Ben Manley: Digital Thoreau” with another article, coming out in the March issue of the Rail, about bagpiper and loud drone musician David Watson’s Striped Light concert series, which takes place in a secret location in Long Island City.

I’ve also enjoyed writing for Mark Gresham at his Atlanta-based classical music source, EarRelevant, where I recently reviewed the highly-anticipated New York premiere of Huang Ruo’s Angel Island.

Writing about music never gets easier. Nor should it. Too often I see music critics relying on the same phrases and elegant, Latinate, multisyllabic words to describe wildly different music. I try to be aware of that trap. But I often fall into it. The purpose of writing about music is a little murky right now. Anyone can review a concert by posting a picture of it with a critical caption to their thousands of followers. If they post a video, the viewer pretty much has at least a limited idea of what the concert was like. Who needs us? What should we do? Whatever it is, it has to be something more than pretty adjectives.

There are so many different kinds of concert experiences and venues and each one has a different feel that we need to emphasize the spaces where music happens. And get people into those spaces. And we have to agree on what the purpose of music criticism is, anyway. Is it to get more people to appreciate a broader range of music? Yes, I think it is. To get people out, experiencing new spaces, new sounds, and meeting new people. Music criticism should criticize, but it should also intrigue. It should be magnetic, drawing readers out of themselves, their parochial imaginations, and their homes.

Music is social. Writing is social. It is all communication. Music criticism must communicate something forward-looking, something optimistic, something magical. It must speak to somebody. We have to agree who we’re speaking to. Are they other critics? Are they people who like classical/new music? Are they people who know nothing of such things? Or is our audience public relations people and agents who will scoop up a neat phrase from the middle of a review to post on the landing page of their artist’s website? We have to decide.

Mingjia

I will leave you with two photos from a January 10 performance by the enchanting Mingjia Chen and the spellbinding Isabel Crespo Pardo (“iiisa”) at C’mon Everybody. Seriously, it is mystical how good both of their musics are. Mingjia’s album, star, star came out from New Amsterdam Records in November and came in at number five on the six albums I chose to include in my Best of Noise 2023 countdown. The song “**_*” gives me the chills every single time I hear it. She performed with Yaz Lancaster on violin and Andrew Yee, a founding member of the Attacca Quartet, on cello. Yee blew my head off with virtuosity, lyrical phrasing, and good ole’ passion. iiisa and their trio, Sinonó—comprised of Lester St. Louis on cello and Henry Fraser on bass—will release their first album in March.

The whole thing was very gay, very beautiful, and very memorable. It was also one of the rare times when the lighting on stage (bisexual lighting, in this case) melds perfectly with the sound. It was criminal how few people were at the concert.

See you next time! And remember, sometimes the best really is noise.

P.S. I’m also a pianist and if you ever want to check out a low quality recording of a recital of Bach, Scarlatti, Liszt, and Grieg I did in 2022, you can check out “Baroque Jewels, Romantic Revivals” on Bandcamp.