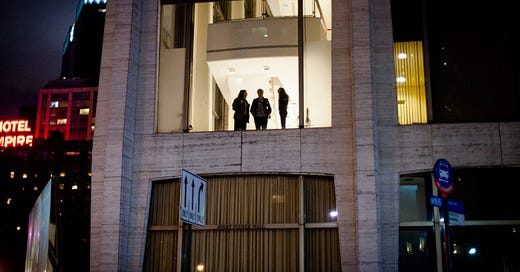

Backstage at David Geffen

Meeting John Adams, disliking his music, failing to vibe with composers

I met the composer John Adams very briefly Saturday night backstage at David Geffen Hall. He had just finished conducting a concert with the NY Phil of his own City Noir, Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten, Copland’s Quiet City, and the New York premiere of Gabriella Smith’s Lost Coast.

He came off the stage and into the carpeted hallway with frantic energy, hunched, holding a pile of what looked like conducting scores, accompanied by his wife, the photographer Deborah O’Grady, before stopping to sign something that an assistant placed in front of him. His composure made me feel unaffected, like I was seeing a guy coming home from just another day at the office. Like I was in fact the interesting one, leaning coolly against the wall, hands in my pockets, long coat, legs crossed. Although, he was wearing a scarf, and I wasn’t…

I was one of the first ones to get backstage after the show, along with a composer friend of mine who used to study with Adams in Berkeley (Young Composers Program), which is why I was allowed back there in the first place. So, unlike the composers and artists who flowed in after Adams made a hasty retreat, I actually got to shake his hand. He looked lively, though older than I expected, like a Founding Father (living up to his name; [his son is a composer too and his name is Sam—can you believe that?]), and had a nice firm grip, more businesslike than artistlike. Which explains why, after he was long gone, the composer David Lang (of Bang-on-a-Can and Little Match Girl Passion fame) remarked that he is “the most professional of us all.”

After Adams left, a number of us stood around awkwardly making chest-tightening, anxious conversation. I spoke least of all, since I really had no business there. This awkwardness isn’t distinct to composers, but I’ve noticed a lot of composers just talk to other composers and no one else. And I don’t hang out with many, so it’s still funny to me to hang around in a group like this. My experience with more ramshackle composers is different. Experimental music folks in Brooklyn are weird, but they can at least hang. As my friend put it: “Ultimately composers walk this line of being introverted as workers but then having to socialize either out of convention or wanting genuinely to chat with people. But the problem is that the concert hall is so transient. It’s hard to chat. To have a real chat.”

On the walk back to the subway (before we learned that the C/E wasn’t running and the L was down because it hit someone; it was a long journey back home), I remarked to my friend that composers who are trained in the academy seem to be trained to care more about music than people. I was going to spin this into an argument about how even though music was one of the classic disciplines within the quadrivium—the basis of a well-rounded, liberal arts, humanities education, that the original universities models like at Oxford and Cambridge were based on—now it seems in the academy music has been completely divorced from other studies. Everyone has heard people talking about the over-emphasis on specialization. The thinking goes that if it weren’t separate from other studies that comprise a humanistic education, then composers would, well, at least be able to talk to people. The kind of education I got, or at least crafted for myself, at my own small liberal arts college. Not that I’m an expert in “talking to people.” Just that, I don’t know, I’m curious about what people have to say.

But I didn’t spin that argument, because my companion is my friend, and all we’re doing is walking to the subway on a Saturday night about to get drunk.

That thread of conversation was interrupted, anyway, when, on the sidewalk, my friend recognized someone. He seemed to be magnetic that night; he ran into a bunch of people he knew.

We passed what looked like a couple. I didn’t think anything of them, but he turned around.

“Excuse me, are you a… music person?”

The guy, short with rigid black hair and glasses, was shocked. “Uh, yes.”

“Are you, like, involved in new music?”

“Yes.” Giving nothing here.

“Do you have any, like, institutional connection you’re affiliated with?” This might sound condescending, but he asked it in a genuinely interested and polite way, only because he himself is affiliated with Yale.

“Um, yeah, I mean I’m here and there.”

“Do you happen to know L— B—?” A musician they might have both known.

The guy said yes.

Now this is usually the moment, in a normal interaction, when the two people connect and either agree to make plans to hang out (even if they never follow up on it, which is normal) or at least exchange contact info. With so much in common, you’d think! And yet, this guy, a composer or conductor or something, gave him none of that.

“I’m sure I’ll see you around some time.”

“Yeah, cool,” my friend said. “Well, nice to meet you.”

And we walked off.

I’m sorry, but if you live in New York you shouldn’t be surprised when you run into someone who you share connections with. It happens all the time. Sure, maybe it was a first date. Sure, it was late on a Saturday. Maybe he just came from a concert of studying or practicing. Blah blah blah blah. Where’s the love of the hang?

Despite all of this, I need to tell you about this concert.

Forget about the Pärt, which was beautiful, even if, as my friend pointed out, it’s absurd how a whole audience claps wildly for just a slowly ascending and descending scale. It’s some scale, though. And even if, after the final bell strike—which should resonate throughout the hall amidst complete silence until the sound has totally dissipated and even after it has dissipated, like the similar ending of Shostakovich’s Babi Yar Symphony, which I heard in Salzburg a couple years ago, surrounded by an audience who held the mournful silence for a solid two minutes (American audiences could never)—someone dropped a program, a sound which someone else heard as a clap, and they started clapping, and then everyone started clapping, ruining what could have been a magical moment.

And forget about the Copland, which Ryan Roberts on oboe and Christopher Martin on trumpet absolutely nailed, both of their sounds purifying the air in piercing, clean declamation.

And, finally, forget about Adams’s City Noir, which I’d never actually listened to, but which was actually the worst piece on the program. “Meandering,” my friend called it, even though he was floored by it, the piece exemplifies what I realized I really hate about Adams’s music, which is this glaciality, like the Titanic sinking. Not quite monotonous or labored, but just like a huge, heavy Magic 8 Ball rolling across the tundra but you can’t see the prophecies through the hole—you don’t know what it’s trying to tell you. This heaviness made me yawn and rue the fact that what I thought was a one-movement work in fact has three movements. I’ll give it to him, though: the seven French horns sure do some damage. I always want live orchestra concerts to be as loud as the music in my headphones, and this did the trick.

Now, having forgotten about all that: One thing I want you to remember is how good Gabriella Smith’s piece Lost Coast is. Like, holy shit.

Maybe I loved it so much because I haven’t heard many pieces of new music at big concert halls for the last couple months (I’ve been more into hanging out than going to concerts). Maybe if I’d been going to more new music concerts lately, I would’ve had that familiar reaction of “It sounds like everything else being written today.” God knows how, to me, that feeling is like seeing an old-friend who’s successful but always makes a big deal out of it when you catch up with them.

But since I can’t know how I would’ve reacted if I’d been a recent regular on the new music circuit, I can only tell you about the two times during the performance when I let out a forceful, astonished, and impressed exhale, the kind of exhale that sounds like you’re about to hock a loogie: “hkkaa!”

Smith’s piece was the best one on the program. It was intricate, suspenseful, “beautiful” (this is the word that David Lang and the other composers backstage used to tell Smith how much they liked her piece), and the musicians looked like they were having a blast playing it (this is something my friend noticed that I only realized in retrospect). I remember the bongo player finishing up a groovy cha-cha solo, hitting the last hit, and walking away with mic-drop swagger—like, “fuck ya, I just did that.” At one point, the whole orchestra reaches a climax then falls down—boom!—in a rapid glissando that made the sound almost visible—like a mammoth falling into the ocean. That was the first time I hkkaa-ed.

The second time I hkkaa-ed was during one of the many suspenseful parts, all extended moments when you’re inhabiting a sound world that’s constantly changing and yet static but you’re on the edge of your seat wondering what’s going to happen next, what extended technique is going to blow your mind. (I especially liked when the trombones hit their mouth pieces with their palms, making a popping noise). The violins were strumming their instruments like banjos, the bassists were rubbing their instruments’ necks up and down, the percussionists were going crazy, doing all sorts of who knows what, while Adams, conducting, had his hands at his side, evidently signifying a passage of improvisation from the whole orchestra. Everyone seemed to be doing something different. And yet it wasn’t noise. It was natural, like the eponymous area in California that Smith sought to portray: Lost Coast in Northern California. Before the piece, she told a story about backpacking there and waking up in the morning to find bears tracks around her tent. Indeed, this section of the piece was gloriously menacing, like a bear walking around Lincoln Center. A very intricate, well-crafted bear.

The energy in the hall after her piece finished was good. Just good vibes. Genuinely happy. I actually wanted to give a standing ovation. And I did. And we did.

She told us backstage that the piece—which is a cello concerto, and I should mention that the soloist, Gabriel Cabezas, played with pure instinct, intuition, and inhibition, like he was accompanying a raucous Cuban street festival—is being performed again soon in Prague, and I’m thinking of starting a GoFundMe so all you readers can pay for me to hear it again. (Alternatively, smash that button down below for a free subscription or maybe sauce me $5/month [or $50/year]!) I hope she gets just as enthusiastic of an audience there.

Your friend’s comment in this context (I was at Thursday concert) points to my general disappointment with new American music that comes out of the academies: the composers can’t tell the difference between gestures and communication. Pärt and Copland communicate, Smith and Adams did not for me.