Piano As Couch: Erik Satie's Proto-Ambient "Furniture Music" in an NYU Lobby

The Village Trip Festival's 15-hour long production of the composer's "Vexations" were one sound among many.

It had been going since 6am. Now it was 11 hours later. I had sat at my desk all day, working on other stuff, imagining who was there and what it sounded like. I spent my time listening to new tracks by Nico Muhly, Endea Owens, Yussef Dayes, and, of course, Olivia. So many different sounds over so many hours. That someone (or, potentially, no one) was listening to the same page of music, played over and over again in what I assumed was a shiny new NYU concert hall in Greenwich Village seemed to me like a purgatory that I was yet to enter. It’s like when you get invited to a party, decide not to go, and then picture what they might be doing without you, but you’re fine with it. No FOMO. Is it a party at the Paulson Center? Who’s there? Yuja Wang? Yannick? Caroline Shaw? Bob Dylan??? John Cage resurrected????? I was willfully missing out.

But now it was 4pm and I decided to make my trek across the river, no Virgil by my side.

The sky seemed to forecast the music I was about to hear. It was almost raining, muggy, and depressingly hot. I bought an Italian sub. I approached the glassy Paulson Center and saw an ambulance outside, lights flashing. I made my way through the revolving doors and into the lobby. The ambulance strobes coming through the thoroughly-windowed space made this communal area frequented by NYU students with ripped jeans and rich parents look like a night club. But no light sensitivity warning was to be found. Only a grand piano near the welcome desk and sign that said: VEXATIONS Erik Satie (1866-1925) 840 Repetitions, 24 Pianists. At first it looked like there was no one at the piano, and I heard nothing. Could this be it?

Then I saw him. Kees Wieringa, the nineteenth pianist of the day. And I heard it. Crumpled, dissonant, sluggish chords, meandering around the center of the keyboard, I took a seat on a swirly padded backless bench, started eating my sandwich, and thought about how I should listen. Or if I should listen at all.

I was conflicted because I knew I was listening to something called “furniture music.” It’s a term that was coined by the French composer Erik Satie, who was a quiet revolutionary known for his time-bending, mystical-sounding, sometimes absurd, sometimes sarcastic, proto-minimalist, proto-background music. You probably know him from his Gymnopédie No. 1, the first of three cradling, relaxing-on-a-rainy-day, slightly sexy slow Dionysian dances. His Vexations, though, have no explicit musical inspiration, content, or goal.

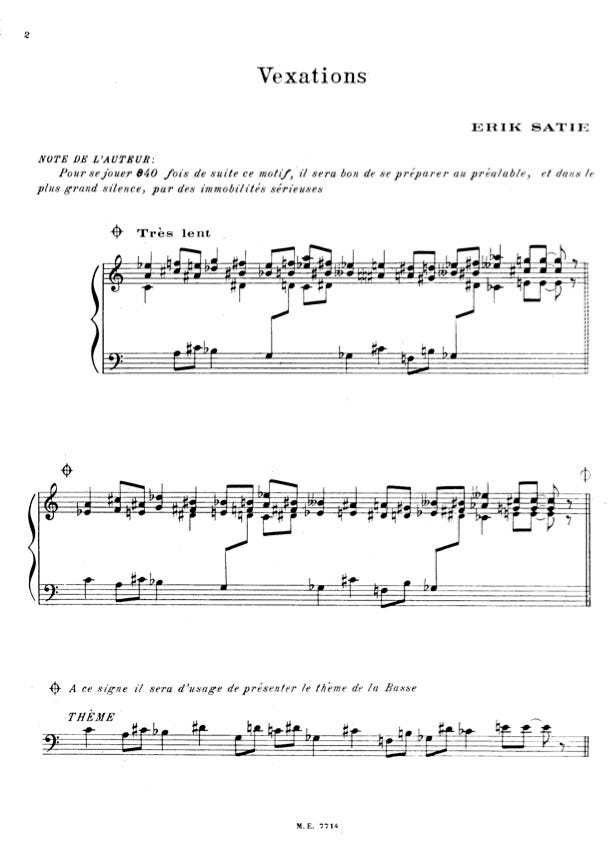

No one even knows why they’re called Vexations. The harmonies are certainly vexing. Harsh tritones — “The Devil’s Interval” — occur throughout, and the mock-Wagnerian theme, along with its accompanying chords, never resolve. We never feel like we’re home. That’s probably why you can listen to it for a while and be tolerably bored instead of kill-yourself-bored like you would be if you heard “Happy Birthday” or “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” — songs that resolve nicely at the end — over and over. Although the creepy, incense-sounding theme does get stuck in your head easily. It’s also weird that the name of the piece is plural. It’s one page of sheet music with two systems and a theme to be played after every system at the bottom (see below). Is one “vexation” equal to one page, and 840 vexations are equal to 840 pages? Or is each chord a vexation, and one page of music contains several vexations?

Satie never indicated that the piece is supposed to be played on the piano, but it’s been done that way ever since John Cage, who rediscovered the work, presented the world premiere on September 9, 1963 at 100 Third Avenue, exactly 60 years ago. Friday’s performance similarly had 24 pianists play this one page of sheet music 840 times. Cage’s show lasted around 18 hours, but some performances go on 24 hours. It depends on how fast you play it — how you interpret Satie’s instruction of “Très lent” (very slowly). The pianists for this performance were playing it faster, so it only took 15 hours. In 2020, for example, Igor Levit, in probably the most exciting classical music event of the early days of COVID, live-streamed his 12-hour performance of the piece. He ate nuts and pieces of fruit and threw each sheet onto the ground after he was done with it, culminating in a carpet of paper around the piano. Thousands of people tuned in, of course. And many stayed for a long time. But would Satie have wanted this?

Probably not. You’re not supposed to listen to this music. You’re just supposed to hear it. Or, it’s music that’s meant to be seen and not heard. Like a couch, or a coffee table, it’s meant to be just part of the room, a mere backdrop for life. Most likely a response to the I-demand-that-you-listen music of Brahms and Wagner, Satie’s furniture music, like Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cakewalk” or “Voiles,” makes fun of the grandiosity of Teutonic titans by undercutting their seriousness. Composer Gavin Bryars called Vexations “a poor man’s Ring of the Nibelungs.” It last just as long as, or longer than, Wagner’s masterpiece, but has no hero, no story, no pretensions. As the French scholar Hervé Vanel put it in his 2013 book Triple Entendre: Furniture Music, Muzak, Muzak-Plus: “[The Vexations] are intrinsically monotonous and can retain the attention of the active listener for only a short span before boredom inevitably sets in.” It’s like watching grass grow, only that the grass never grows.

But I decided I would listen. As I began to tune out the noise around me and focus on the piano, I started to notice subtle differences in how Wieringa played each repetition. At first, I noticed he was using a moderate amount of sustain pedal, giving a slightly blurred, mystical air to the music. Another time, I noticed that he emphasized the line in the left hand so much that the right hand was almost inaudible. He played with timing, too, varying when he would attack a chord or begin the next repetition by just a fraction of a second. Once, he hit a wrong note, which I welcomed, since it enlivened my attention and staved off boredom for a minute or two. Hitting a wrong note in this music is like hitting a wrong note in Bach — everything is so thoroughly worked out (in this case, you hear the same notes every time, so you know what it should sound like) that it really stands out. Toward the end of his repetitions, Wieringa used even more pedal, making for colors that reminded me of Scriabin.

I happened to be sitting next to the pianist who was about to play next, Helen Jiang, an adjunct faculty member at NYU Steinhardt. I asked her how she practiced a piece like this, that just repeated over and over again. She said she practiced it just like she would practice any other piece. Hmm… I asked her if she had an overall conception or plan of the piece before playing, and she said no. Hmmmm.

Jiang eventually got up and approached the piano. Wieringa finished the last repetition and as he held the last chord in his left hand, Jiang took over the chord, continuing to hold it down as Wieringa took his hand away and walked off. Jiang continued right from there, losing no time. Her playing began with no pedal at all. It sounded classical, mannered and straightforward. But then it went baroque and got drier, less mystical, and more declamatory. She started to use the pedal about ten minutes in. She began one repetition in such a way that it actually startled me, and I began to think that she was trying to compete, mockingly, with the din around her.

In the hour I was there, the sounds of the lobby ebbed and flowed and the ambulance lights continued to flash. Cops asking a paramedic questions at the front door, just feet from the piano, about whatever incident they were responding to, talking into their walkie talkies, which beeped. The sound of a sports kid saying he wants to get down to 130 pounds. The sound of girls scream-laughing. The sound of an entrance beep at the welcome desk at the other side of the lobby. A guard stopping a student — “Hey!” — who doesn’t have their student ID. And of course the general sound of cars and conversation. And we must not forget the sound of page-turning on the piano. Dedicated listeners cycled in and out, never numbering more than ten or twelve at any one time. All this was a perfect setting for furniture music, and I think Satie would have gotten a kick out of it.

The fault in Levit’s 2020 performance was exactly that it put too much focus on the music itself. People tuned in especially to hear it. He played with no one in the room. It seemed to be an expression of the unbearable isolation of the time, but it actually totally negated the purpose of the music. If he really wanted to be faithful to Satie’s intentions, he should have told his fans to put on their headphones for 12 hours while they go about their day, and to not just sit down and stare at him play.

But sure, it was a feat. And only a few pianists have done it alone. One of these pianists was in the audience. Richard Cameron-Wolfe had been the sixth pianist of the day to play, but he told me he had been there since 6am, when it began. Cameron-Wolfe, who now focuses on composition, has given four uninterrupted, solo performances of the Vexations, some lasting 24 hours. He’s done them unassisted, and said that he would use an attendance clicker to keep track of which repetition he was on. That tickled him because it added another “sonic element” to the performance. He emphasized how difficult the piece is, despite it being one page and sounding relatively simple. It’s the visual element of the page, he explained, that is confounding at first. He took out his score, which was pasted on a piece of cardboard, and pointed out the A double-natural-sharp in the first system. “How do you interpret that?” I asked. It’s just an A#, he said, but Satie is playing with us, confusing us, vexing us. Why, he goes on, did Satie choose to put the theme straddled between the bass and treble clefs. Why couldn’t he just leave it in the bass?

Everything about the Vexations are confusing. But they’re harder to look at than to listen to. And Friday’s performance of the Vexations was easy on the ears. I think this was right way to do it. The music was just one part of the general noise of the city. No effort was made to isolate the music. All was music. All were players. Jocks, e-girls, coaches, nerds, old men, and outcasts all walked by. Few listened. All heard.

Perfect.