Striped Light Goin' Messin' Up My Mind

Peeling my face off the floor after David Watson's "Striped Light #2" concert in Long Island City

I rue the day when I got that trivia question wrong.

The one that went something like, “What band inspired more garage bands than any other?” I thought back to the ’60s and immediately thought of The Kingsmen, whose “Louie, Louie” had lyrics that were famously so hard to understand that the song was actually banned from the radio. It also sounded absolutely terrible, sound-quality-wise. That’s what made it so great. Anyone could make those sounds, I thought. So teenagers probably thought, “I can make those sounds,” and they started their own band. So I convinced my team to put down the Kingsmen. I was shocked when the announcer said the answer was actually The Velvet Underground.

How COULD I??? I love that band. In a very serious way. In a way that made me feel like a fake when I got the question wrong. But of course it was them! Who knows where the announcer got his data, but both these bands certainly did have the “anybody can do that” quality. That’s what I imagine was so inspiring about the (mainly) two-chord “I’m Waiting For the Man.” Not everyone had the Velvets’ magic, but they did have guitars, drums, and ears. Rock ’n roll was the beginning of unskilled, amateur musicians having a shot at celebrity status. Forget the conservatories and the voice lessons, the years of gigging and improvising with jazz bands, forget practicing; plug in the amp, light up the room with noise, and watch the ladies swoon.

This “anybody can do that” quality is also apparent in a lot of reactions to experimental music. In fact, my dad said exactly those words Monday evening, when I brought him to the second concert (I wrote about the first one here) in David Watson’s “Striped Light” series, which, once again, ripped into the cold concrete walls of a secret location in Long Island City with a sound that was, sometimes, as vicious and maddening as death metal and, other times, as serene as the drone of a tanpura on a hot day in Bangalore.

Anybody can do that—why would he say something like that? So diminishing, and so negative, so square, such a put-down. Can’t you just chill, dad? These are Real Musicians™. Let the people do their thing! Why you gotta be such a downer? Anybody? Well then, how ’bout you get up there and show ’em?

Why would he say such a thing?

Well, let’s see.

Henry Birdsey, from Vermont (and looking like it; yes, he had a brown beanie on), was up first. He sat down in a chair facing the audience, microphone mouth-height in front of him, and as the white light shined on him from the floor, casting his shadow onto the white wall behind him, he dumped two, maybe three, harmonicas into his lap.

He brought the first one gently to his lips, touched it to the mic—head and harmonica now one unit basically—took a deep breath, his shoulders rising like two cranes, and started to slowly, evenly, blow his air out into it. It droned, crescendoing and diminuendoing like a foghorn run through a feedback loop. I couldn’t understand how he held his breath for so long. His breath control was brilliant. He sometimes played one note and sometimes a couple, allowing the overtones to resonate, enveloping me in sound. He did this with the other harmonica(s), too. Each one had a slightly different timbre. I closed my eyes and saw shapes, floating and contorting in concert with the pulsating, overlapping overtones. A baby sat with his father in the front row. He didn’t cry. Neither did the baby.

My dad had that white-person-smiling-when-they-pass-a-Black-person smile on his face when Birdsey finished. A smirk that told me he’d trade anything to be listening to Frank Sinatra at this exact moment. But I give him credit—he clapped. A Sicilian man who grew up in Bensonhurst, clapping at a beanie head from Vermont playing the harmonica. Might be a first. My dad even thought it was “soothing” and “hypnotizing” after he got over the initial shock. I loved it, and would gladly have listened for longer.

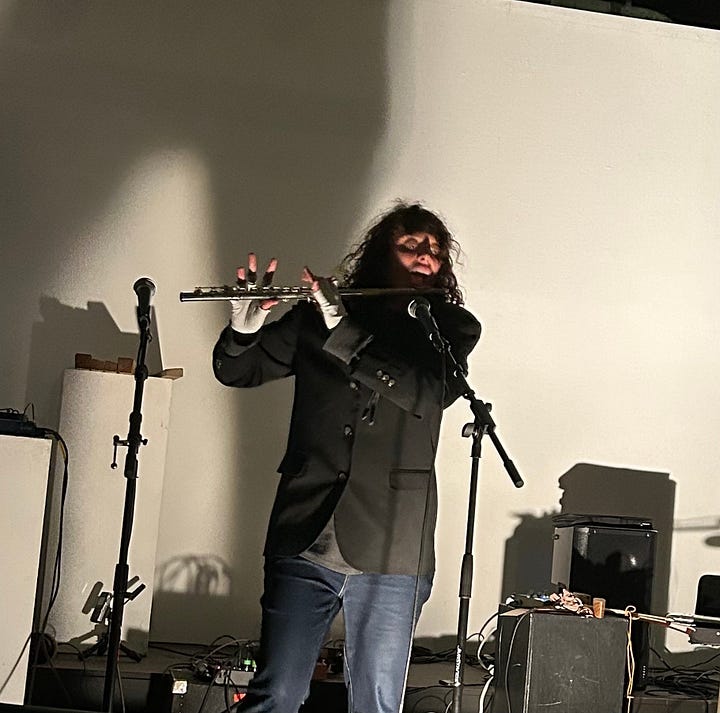

The next act had me in pieces. Brooklyn-based flutist/vocalist Ka Baird and Laura Cocks (same vocation and location) got on stage with two flutes (plus a bass flute for Cocks) and a couple mics for their first ever duo performance. The approximately half-hour performance was literally jaw-dropping. They both started on flutes, violently fingering the keys, blowing into the instruments like they were candles that wouldn’t for the hell of them blow out, and frequently screamed, elongated, high-pitched, like monkeys whose toes you stepped on. I couldn’t believe two humans were making so many sounds. But the sheer amount of noise wasn’t all.

It was the gestalt experience, a hellish soundscape that had me wishing for an exit to purgatory and a trap door to hell’s deeper bowls at the same time.

Baird put their flute down and took up a loose mic in their hand. They whipped it across their mouth as they shushed into it, the sound fading in and out with the thrust of an F-16. Their long, curly hair draped over their face, and the white light projected their shadow behind them. They started moving more nervously, clutching the mic in their fingerless-gloved fists, as they death-metal screamed into it, adding bass to the Cocks’s cacophony.

Baird hit the mic with their fist. They shoved the mic under their sweatshirt and beat it, mimicking a beating heart, or someone trying to get a giant cockroach bug out of their clothes, or both. At one point, they marched in place before getting more gremlin-like. I felt like I was watching some grimy, hostile goblin in a Medieval-period video game. They took another mic, bashed their two heads together making huge UMPHs. They clasped one and pretended, it seemed, to axe an invisible fell tree or a splayed body.

Making crackly and slurpy mouth sounds that reminded me, variously, of frantic insect legs and lizard tongues, they began to reveal a narrative. The two engaged in a battle of sorts, with Baird at one point taking their flute and standing in a baseball-batter stance, while Cocks spit air into their bass flute. Baird added effects to the mics, swinging two of them in front of the audience, catching our silence, and turning them into cosmic whooping noises. All the while Cocks kept up, with their own technically virtuosic improvising, which was often overshadowed by Baird’s antics. It didn’t matter, though. Cocks was a good straight man, and the duo balanced out like fire and fuel. It was one of the most rock ’n roll things I’ve ever heard and seen.

Legendary improvisatory vocalist Shelley Hirsch, who has collaborated with Baird, was in the audience, bright green hair aglow. I had the sense she was proud.

My dad clapped very slowly when they finished. “I was gonna pick up the phone to call an exorcist,” he said, after a few days of processing the concert. “Too animalistic.” “Anybody can do that.”

I shot back, “That’s what makes it so good!”

“I looked around the room,” he said, “and a lot of people seemed to be taking it very seriously, so I guess I just don’t understand.”

“I don’t understand, either! You don’t have to understand to enjoy it! It’s so great because there is nothing to understand; it’s just happening.”

“I guess I just don’t understand.”

So, what. Maybe anybody can do that. But will they?

Would you?

The last act was, to my surprise, my dad’s favorite. The Daxophone Consort, made up of Daniel Fishkin, Cleek Schrey, and Ron Shalom, teamed up with Yo! Vinyl Richie to form the “Vinyl Consort.” A daxophone is a “thin wooden strip played with a bow,” according to the group’s website. “The instrument’s sound, somewhere between a cello and badger, ranges from furtive gurgles and delicate whistles to wild screams.”

First, Vinyl Richie started turning tables, cutting and pasting together snippets from classics records, scratching them, slowing them down, looping them, speeding them up. Some had sax solos on them, others had 1950s-sounding TV commercials.

“I hope he can fix it,” my dad whispered to me. The funny thing is my dad got his start repairing radios.

The three daxophonists processed solemnly down the middle aisle. They wore black-framed sunglasses with white nylons pulled over their heads like burglars. They took themselves too seriously. I wasn’t a fan of the albino dementor persona thing. It’s excessive, and over-convincing. The sound of the instruments really didn’t do anything for me, either. There is a fine line between wood shop tool and experimental instrument, and the daxophones inched too close to the former.

The daxophonists took away from the greatness of Richie’s mixing. At one point, a man’s voice from a TV commercial said on one of the records, “A hearing aid will take some getting used to,” which was well-timed and funny. I would’ve preferred to listen to Richie alone. Part of the problem also was that there was very little energy or propulsion in their performance, and no one seemed to be the leader. Since it was improvisatory, there were a lot of lulls, but not substantive lulls. I got bored.

And yet, it was my dad’s favorite performance. It had structure and rhythm, he said. True, Richie did make some loops with repeating patterns. At least it had some form, he said. I didn’t agree, but, hey, my dad clapped at a normal speed.

His, “anyone can do that,” stuck with me. He said later on it was like watching children playing with toys. But I say, how beautiful is that? Wordsworth, after all, wrote, “The child is the father of the man.” And yet my father couldn’t fathom getting anything out of watching children playing. And, let’s be honest, not just anyone can do what the musicians at Striped Light #2 did. It just sounds that way.

And that’s the crux of an expression (or I guess it’s really a flowchart) I came up with during the concert that I’m quite proud of. Here it is: “I don’t understand it” → “Anybody can do that” → “I can do that” → “I will do that” → more creativity is brought into the world. And isn’t that the ultimately goal? Unless you argue that what happened Monday night isn’t creative. But you’d be insane.

Maybe when you go to a concert like this, your first reaction isn’t to be inspired to try something like it, or to be creative at all. But, think about it, if you went to see a performance of a Liszt piano concerto or a Bartok violin concerto, or any other “difficult” work, would you leave saying, “anybody could do that”? No. You’d leave saying, “I could never do that.” And you never would. And that, I think, would be a shame.

At David Watson’s Striped Light concerts, at least you are engendered with the spark of creativity. Whether you choose to act on that spark is up to you.