Help Me Uncover the Lost Story of Wittgenstein's Favorite Composer

The first in an ongoing series of posts dedicated to my research into Josef Labor. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to view future posts on the subject.

On the morning of October 8, 1901 – a temperate autumn Tuesday in Vienna – a man wept at Alma Mahler’s feet. She, 22, was still Alma Schindler, and he, 58, was blind. It was the first time, but not the last, that she would have a man in tears.

But this time was different. Alma had studied composition with Josef Paul Labor since the age of 14. At eighteen (when she started to keep a diary), she called him “really sweet.” At nineteen, she thought he was the “wisest man on earth.” At twenty, she called him a “martyr for his art,” even if he wasn’t monumental or revolutionary. He was her “fatherly friend.”

By the time she was twenty-one, Alma was studying with both Labor and Alexander von Zemlinsky, a teacher (and very soon the brother-in-law) of Arnold Schoenberg. Zemlinsky would become Alma’s obsession. But she had not told Labor of her new instructor, and the guilt was eating her up. She thanked God he was blind, lest her countenance belie her words. She still worried that he would “hear” that she was spending “every free moment working for the quizzical praise of another teacher.” Now, after a spring and summer of failing to please Labor with her compositions, she had chosen this day to admit her infidelity.

“I see no need for you to study with me any longer,” Labor said, wiping away his tears.

“I’d sooner give up Z. than you,” she replied, assuring him that she would continue studies with Zemlinsky only if he didn’t object.

“I can’t do it,” he said. “Either Z. or I. But both – no.”

In the end, Labor’s objection didn’t matter. His operatics, which would surface again, were in vain. She was destined as if by magnetism to choose Zemlinsky. Labor was devastated. He knelt and kissed her hands. He had seen promise in her, as a composer and a friend. In her diary, Alma took note of the day when they left each other forever. But not before realizing that she hadn’t learned “all that much.”

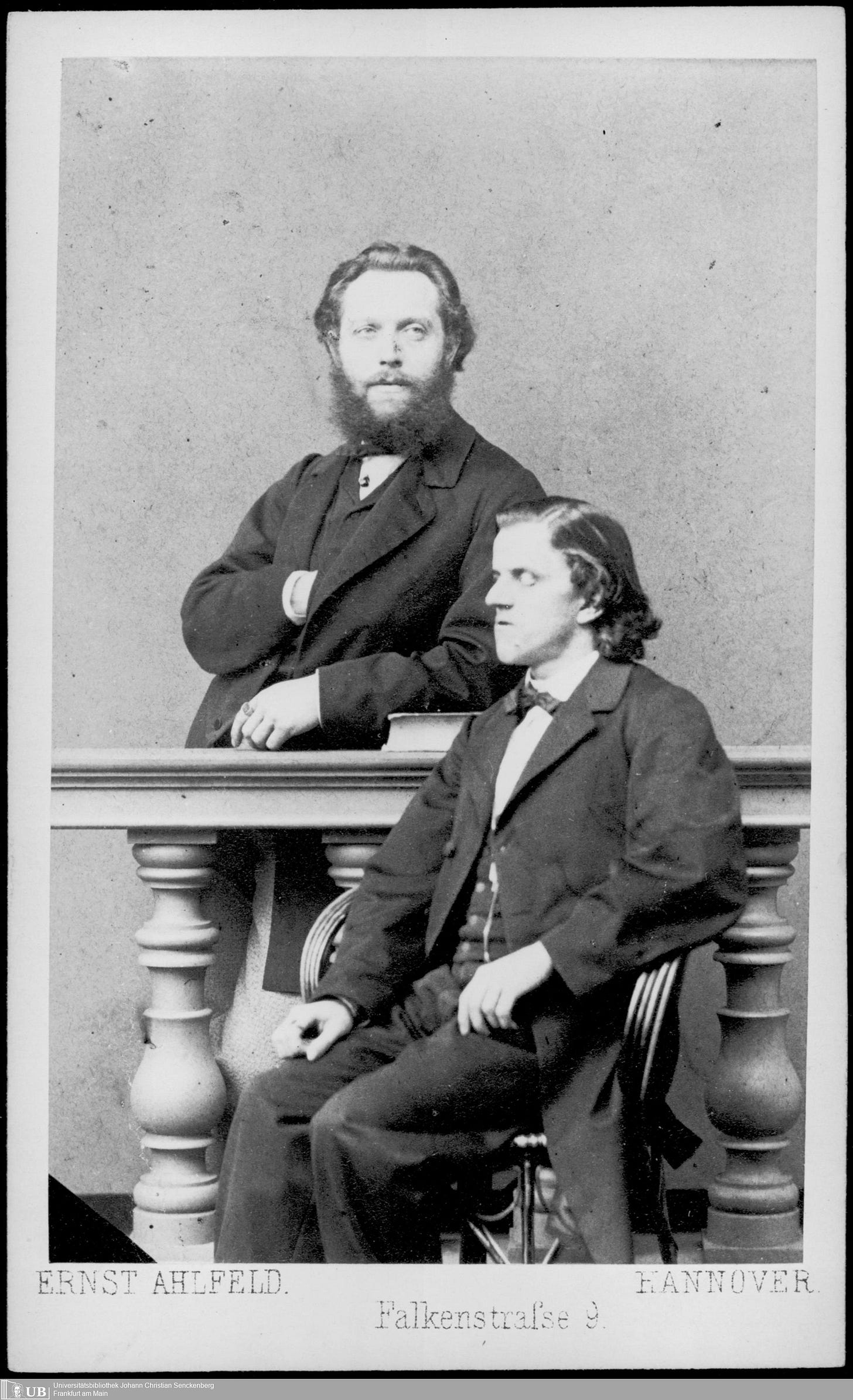

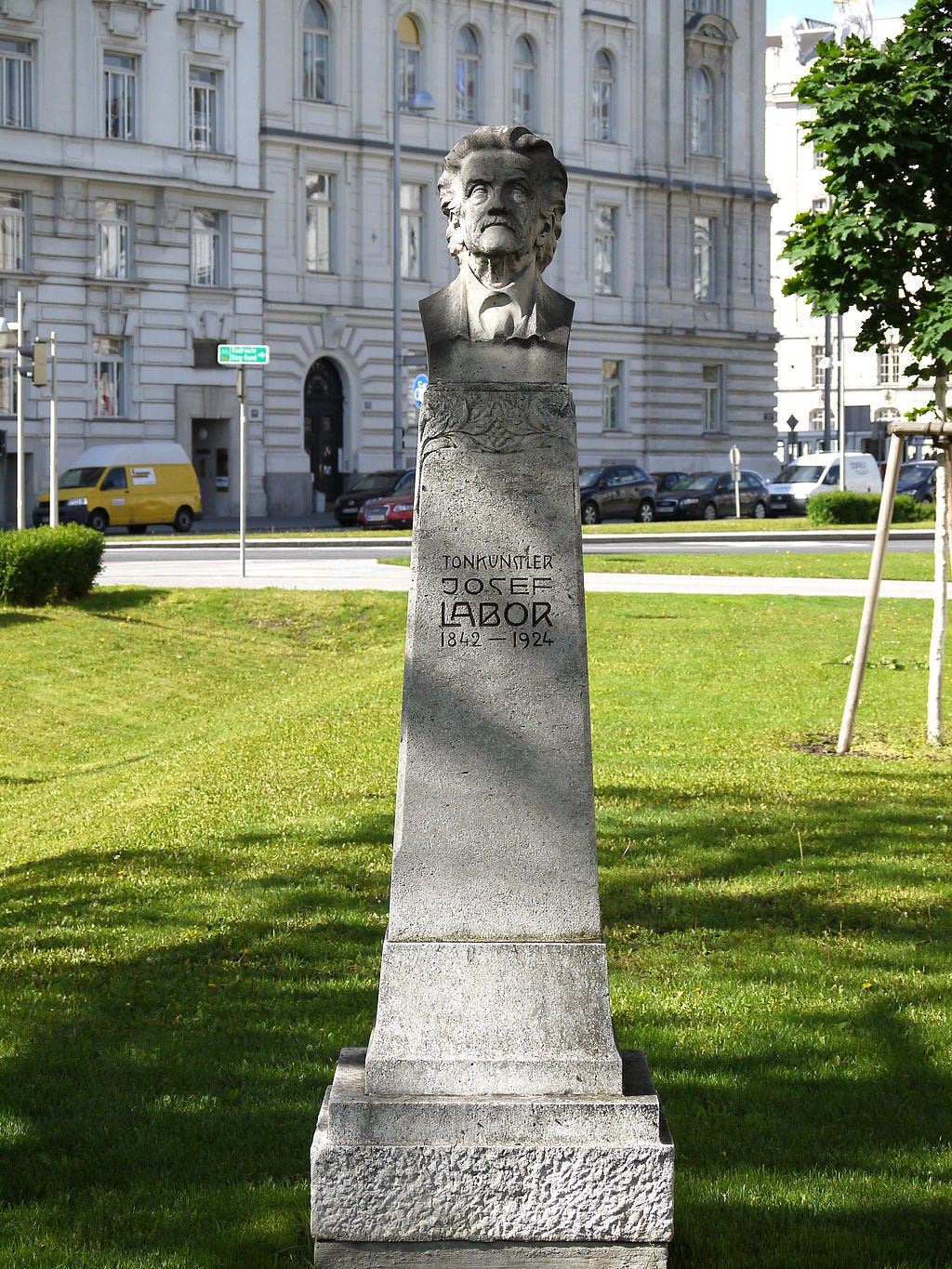

Josef Labor (1842-1924) — touring organist and pianist, neo-Brahmsian composer, friend of King George V of Hanover, Schoenberg’s first teacher, darling of the Wittgensteins, nucleus of turn-of-the-century Vienna’s musical conservatism, etc. — is one of the most fascinating examples of mediocrity in the history of music. He is also one of the forgotten about. And yet, his social circle, musical style, and taste give us an unparalleled window into the world of that large swath of Viennese bourgeoisie who balked at the innovations of artists like Schoenberg, Klimt, Kokoschka, and the Secession as a whole. At risk of being crude, we could call them: the Recessionists.

I first encountered Labor in Ray Monk’s definitive biography of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. According to Monk, Wittgenstein was fond of naming Labor in his list of — get this — the six “great” composers, alongside Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms. In fact, neither Wittgenstein nor David Pinsent, the philosopher’s lover and the dedicatee of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, are on record admiring any music past Brahms except for Labor.

Well! I thought. Who the hell is this guy? The greatest philosopher of the twentieth century names Josef Labor as one of the greatest composers ever, and I’ve never heard of him? Is this some kind of joke? Or, is Labor’s music some kind of lost treasure trove? I had to listen.

I went to Spotify, which lists five albums of Labor’s music under his artist profile, including one released in January. Naturally, I selected the newest album. The first track was the first movement of his Piano Quintet (Clarinet Quintet) in D Major, Op. 11 (1900).

1900: Sibelius’s tone poem Finlandia premieres in Helsinki, Elgar’s oratorio Dream of Gerontius premieres in Birmingham, the first two sections of Debussy’s stunning Nocturnes premiere in Paris, the second and third movements of Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto premiere in Moscow, Mahler’s fourth symphony is heard for the first time in Munich, Puccini’s Tosca is staged for the first time in Rome. Schoenberg is beginning work on the Gurre-Lieder, but hasn’t written anything atonal or twelve-tone. Freud has just published The Interpretation of Dreams. Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 had premiered nine years earlier. We are on the precipice — Romanticism is waning; Modernism is incubating. Could Labor’s music anticipate Modernism? Is he a great late Romantic in company with Mahler, Strauss, and Schoenberg?

I pressed play.

The first thing I hear is a piano playing a melody. It begins in D major. A grand, swooping, ascending arpeggio accompanies the melody as it falls, step by step, melancholy, youthful, Mozart-like (I’m reminded of the Adagio from the Gran Partita), and oh-so-singable. It sounds like Brahms, but not exactly like Brahms. The same kind of coordinated melody and accompaniment, the effusiveness, the richness, the heaving anticipation, the unexpected but welcome tonicizations (i.e. modulations not lasting long enough to be full modulations), the carefully placed ornamentation — it’s all Brahmsian.

Neither Wittgenstein nor David Pinsent, the philosopher’s lover and the dedicatee of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, are on record admiring any music past Brahms except for Labor.

But something is off. It’s, dare I say, boring…? Yeah, no, that’s what it is. But wait, now a clarinet enters with a minor key flourish — and voila! the two are playing a wonderful duet with strings in the background. Now I’m in it, and we seem to be off. The rest of the movement is a continual development. You don’t often get the feeling of “oh, I’m home” or “ah, now my ears can relax.” No, you don’t get a break. The sumptuous flow, with expert voice leading, A+ melody-writing, and balanced parts can either fascinate you, as you listen to all the twists and turns that this highly proficient (what a boring designation) composer concocts, or you turn it off because you want to shoot yourself.

The first time I listened, I felt a bit of both. It wasn’t my favorite thing I’d ever heard. Plus, I knew about the year 1900, and what it meant in Vienna. I knew artistic revolutions were about to burst on the scene — the secessionists, the serialists, the psychoanalysts. It felt like I had entered a time warp. It sounded (at first) like music from 1850, not 1900. And it felt so monotonous, heavy, bland. Not forward-looking at all. This was the music of choice for the philosopher who gave birth to twentieth century Western philosophy.

Is this some kind of joke, Ludwig? I asked the heavens. Really? This guy? One of the greats?

Labor, I learned, was not just a favorite of Ludwig, but a favorite of the entire Wittgenstein family. He basically owed his career to their patronage. They “held him in enormously high regard,” in the words of Alexander Waugh (The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War). He was essentially their court composer.

Ludwig tried to get a Labor work performed when he was at Cambridge, but failed. Ludwig and his friend Rudolf Koder would play Labor clarinet sonatas together. Labor is even buried opposite Ludwig’s mother.

What struck me most was Labor’s connection to Ludwig’s brother, Paul. Paul Wittgenstein was a promising pianist who studied with Labor but famously lost his right arm fighting in World War I. Nevertheless, he went on to have a successful career as a left-handed pianist, commissioning works from Ravel, Richard Strauss, Hindemith, Prokofiev, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, among others. But it was Josef Labor who wrote the first left-handed piano piece for Paul. And the piece just so happens to have been the first ever piano concerto for the left-hand, preceding Ravel’s by fifteen years, and Hindemith’s, Korngold’s, and Franz Schmidt’s by eight years.1

Schoenberg hoped to program Labor’s Clarinet Quintet at a Society for Private Performances concert.

Both Paul and Ludwig, like Alma Schindler, adored Labor as a father figure. Ludwig once wrote to Paul that their shared love for Labor’s music was the thing that bound them together. Paul called Labor a “master” composer who was “underestimated.” So it’s not surprising that Paul, writing from a prisoner-of-war camp in Siberia, sent off a letter to Labor, asking for a composition. The composer replied saying that he was already working on one. Some speculate that Ludwig had given Labor the idea beforehand. Either way, it was 1915, and the piece was ready.

Konzertstück für Klavier und Orchester in form von Variationem (Concert Work for Piano and Orchestra in the Forms of Variations) was finished in 1915, according to the autographed manuscript I obtained from the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Paul premiered it not long after, at his stunning comeback recital. He played it at least three times, probably more.

I read through the piano part at home, knowing that this was likely the first time anyone had played this music since Paul performed it in Vienna on November 17, 1929, in a concert conducted by Anton Konrath. The sound is, once again, Brahms but not. It has effective tonicizations, schmaltzy climaxes, fascinating fours-against-fives (quadruplets against quintuplets), and some elegant writing for strings. But I haven’t had time to make a detailed analysis or play through the whole thing. I haven’t even scratched the surface of this lost, unprecedented work.

That’s where I need your help.

I want this research to go on. There is more to find out about Labor, and more to be discovered in his music. But I am going to have to pay to play. I’ve already paid the Austrian National Library for scanning and sending a PDF of the concerto manuscript to me (thanks to Prof. Doug Johnson, my dear friend, for helping with that). There are libraries to travel to in the United States and Europe (especially Vienna) to get the full story. Plus, I want to some day get a real performance together — orchestra and all — to revive the 1915 piano concerto!

If I’ve piqued your interest, please consider signing up for a paid subscription to Evenings with the Orchestra: $5 per month, $50 per year, $150 for founding member. You will be contributing directly to my research efforts and to more revelations about Labor and his Vienna. You will be privy to original research that no one has done before. From now on, most posts about Labor will be available to paid subscribers only.

Stay tuned to learn more about Labor’s relationship with Alma Schindler, why Wittgenstein liked Labor’s music so much, why it fell out of favor, why Labor was so important to so many Viennese composers, and how his contribution to blind musicianship is inestimable. Most importantly, let’s find out together what Labor’s life and work reveal about Viennese Modernism (Hint: Schoenberg hoped to program Labor’s Clarinet Quintet at a Society for Private Performances concert).

I’ll leave you with a loving excerpt from a 1922 letter that Schoenberg wrote to Labor on his 80th birthday:

Esteemed Master Labor, allow me to offer you (belatedly, because I do not know your address) my heartfelt congratulations on the beautiful celebration of your 80th birthday and assure you of the unwavering duration of my veneration and gratitude. I will always remember that you were the musician who, first and with sufficient authority, seriously encouraged me in my musical attempts.

Get on board for the Labor revival, and help turn my labor of love into a Love of Labor Lost.

Thank you.

Two things: First, Maureen Buja, in a piece for Interlude last month, incorrectly stated that Labor’s 1917 Piano Trio No. 1 was the first work he wrote for Paul. Maureen Buja, “Writing for the War Wounded: Labor’s Piano Trio No. 1,” Interlude, September 18, 2023, https://interlude.hk/writing-for-the-war-wounded-josef-labor-piano-trio-no-1/. Second, Michael Davidson’s 2008 book on piano playing for the left hand makes no mention of Labor at all. Michael Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008).

"This was the music of choice for the philosopher who gave birth to twentieth century Western philosophy. Is this some kind of joke, Ludwig? I asked the heavens. Really? This guy? One of the greats?" This reminds me of an article I read a long time ago in which the author describes going to a dinner party where he meets this new couple. As he converses with them, he sees their taste in art and literature is very forward-thinking. Once the conversation turns to music, however, they start gushing about Yanni and how wonderful his music is. The author wonders why their taste in music is the equivalent of velvet Elvis paintings. Clearly, this phenomenon wasn't limited to the late 1980s...