Please Don't Stop The Music

The fourth night of FourOneOne's Out Music Festival - lemme live it again

The show always goes on, especially for experimental musicians. It’s the DIY spirit, after all, that keeps the art on its feet and often on its toes.

FourOneOne, formerly known as Shift, is an experimental music series. For a year and a half or so, its home was 411 Kent Ave., a quaint repurposed firehouse in Williamsburg. Its concerts were curated by bagpiper and Knitting Factor alumnus David Watson. But in October, the building closed. It will be demolished and rebuilt and eventually FourOneOne will return some time next year, according to program coordinator Che Chen. (Shouldn’t we be out there protesting the demolition?) Luckily, we don’t have to wait until 2025 to hear superb, invigorating creative music.

Right now, FourOneOne is back. This time in the East Village. From January 29 through February 4, their first annual Out Music Festival, subtitled “The Future is Pissed!”, is happening at Theater for a New City. The fest was set up in collaboration with Arts for Art, an organization supporting free jazz, and it is offering an absolutely killer lineup. I’m particularly excited for this Sunday’s 3PM bill, which features bassist Luke Stewart, poetry by Raymond Nat Turner, and the William Hooker trio. This isn’t all FourOneOne is doing while away from 411 Kent. Trumpeter and composer Graham Haynes is slated to host masterclasses, conversations, and performances in a residency that will run from March 7 to April 15.

Between the first and second sets last night, I heard a man behind me whisper to his seat-mate that free jazz is all about “every man to himself”—that it’s an individual vocation. Maybe he’s right, I don’t know—the jazziest I’ve gotten on the piano lately has been Joplin. But if last night was any indication, that man is wrong. If you listened at all to the musicians, you would have noticed that the nuances of what they played showed their intense attention to each other’s sound and their careful managing of their group coalescence.

First up was a duo between Darius Jones on alto sax and Tomas Fujiwara on drums. This was my favorite of the two sets I stayed for (I left before Joe McPhee and Jay Rosen, unfortunately). They coalesced perfectly with just the right amount of individual departures on each of their parts. Fujiwara’s drumming was absolutely exhilarating at its most furious and poignant, even sensitive, at its most serene. He had imagination, intentionality, and a surprising bag of tricks.

Included in his toolbox was one particularly memorable sequence of fills/rudiments that he repeated dozens of times. He would use both sticks, in unison, to hit the snare and the tom maybe seven or eight times, then crescendo to forte, then rapidly roll both sticks on the snare, crescendoing even more, before ending with several unison hits on the snare drum. And then he would start it over again. I won’t even try to guess the meter he was in, if there even was one. It was so original and so tight that it almost seemed practiced, or part of a written composition. But he was composing in real time.

Jones started off the set with squeaks but soon mixed in smooth repeated rhythms made of alternating intervallic motifs that reflected each other, like a sixth looking at itself in a mirror lake. At one point, for at least five minutes, Jones repeated one note over and over again tenuto, while Fujiwara launched into the fills I described above. The thought entered my mind that maybe Jones was trying to use the saxophone for accompaniment by keeping his role minimal, acting like a bass player and grounding the beat for the soloist, who was Fujiwara in this case. It was a role reversal that was as fascinating as it was satisfying. With Jones’s more saturated, loud, rapid finger work, I got the chills several times, feeling tears welling up in my ducts—before he dashed my sentimentality by moving into a different, calmer texture. Right on.

Throughout, there was that Grand Pulse—the kind that reveals itself when you hear great improvisers. Even if you can’t find the down beat or the time signature, you somehow move to the flow. And when I looked around the room, I saw everyone was feeling it differently. Some steadily bobbed their heads like they were listening to a straight-forward rock song. Others rotated their cranium and craned their neck in small circles as if in a trance. And still others, like the kid next to me, moved his head so vigorously and tapped his foot so hard that he shook the seating platform, jiggling my chair, and I had to tell him to stop, mid-performance. But it’s all valid. And it all proves that you don’t need a “beat” to feel the groove.

Don’t kill me. I had not heard of Reggie Workman until last night. I know I have a lot to learn. And I love learning it. Especially when I learn that he played with John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Art Blakey, Thelonious Monk, Wayne Shorter, and more, and has a huge discography. If you haven’t heard of him, good. You, like I, now have got a whole lot of music to listen to.

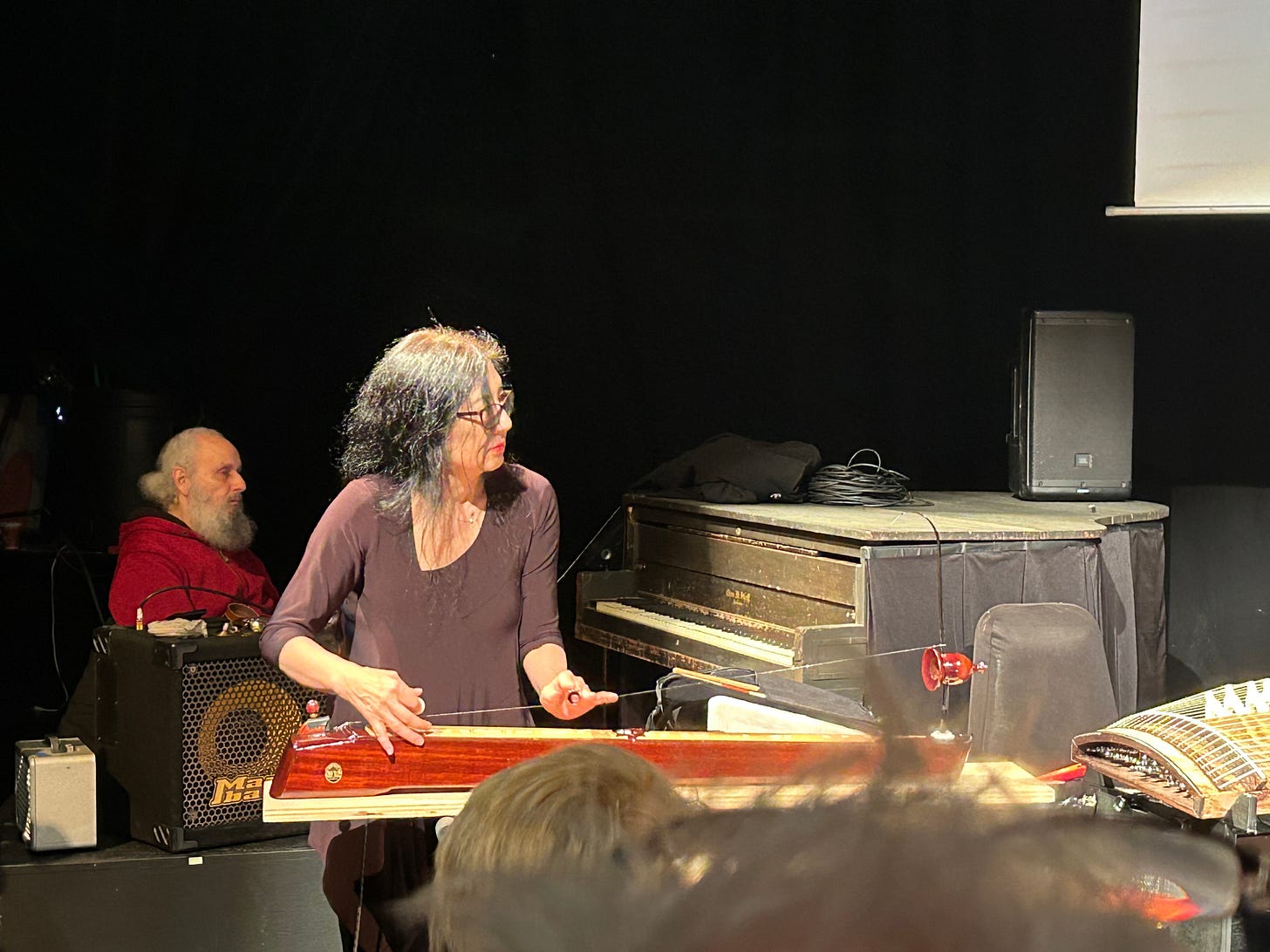

Workman teamed up with Gerry Hemingway on drums and Miya Masaoka on koto and monochord, which at times could’ve been mistaken for an electric guitar. The trio evoked storm sounds, echoed faint whispers of smooth jazz as if bleeding through walls, leaned into the beauty of sound for sound’s sake, relished the silence that filled the stage as each of them decided their next moves, and actively appreciated what their colleagues were playing in the moment.

Hemingway began on vibraphone, which he erratically and unpredictably struck, hitting individual bars, gliss-ing, and executing thoughtfully dissonant chords. He moved to the drum set, exploring his kit like he had never seen it before, hitting it in places not “meant” to be hit. Masaoka started by scratching and plucking her koto as well as brushing the wood of its body—its sides and its undercarriage. Workman looked at peace, smiling many times when he found a moment of synchronization with Masaoka in particular, if they happened to strum the same note or use the same extended technique, like plucking under the bridge. On his right foot, he wore an anklet of bells, whose effect he used sparingly, getting a laugh out of the audience with a few hesitant stomps.

The most magical moment came after Hemingway interjected by blowing violently, erratically into a hollow metal bell of some sort, signalling Workman and Masaoka to stop playing. Hemingway then slowly shifted to humming into it, muting the front with his right hand. Then a serene depiction of the natural world ensued.

Hemingway sounded like a wolf at the edge of a distant snowy field. Workman walked up to the mic carrying a rainstick. He tilted it forty-five degrees, and a shutter ran through my body. I closed my eyes and was in a different place. The tundra? The desert?

Masaoka started in with gentle plucking on her monochord—one of the oldest instruments known to man. It was amped up with effects pedals and had a beautiful wooden finish with a sort of whammy bar at the end. Hemingway started hollering about the cruel winter wind that nonetheless won’t stop him—whoever the character was who he was playing—as he clawed at the surface of the vibraphone. His exclamation was the only bit of vocals. Howling, rain, wind, sand, trees rustling, maybe some small animals softly wining (Masaoka). Workman took a spring drum and rattled it in front of a mic. Back turned to the audience, he hit some finger cymbals with a mallet, which lay on a table behind him. He clinked a tiny glockenspiel. The players had created a space—an environment far away from the blackbox theater where we sat—in time.

In Composing While Black: Afrodiasporic New Music Today, a compendium of essays published last year by the German house Wolke Verlag and edited by George Lewis1, Columbia professor and artistic director of the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), the music theorist Scott Gleason describes a composition of South African composer Andile Khumalo as inviting an “exploratory, non-teleological listening” experience. He goes on:

[R]ather than experiencing a series of events which we demarcate by point A, point B, etc., and then triangulating a past, present, and future, Khumalo’s musical journey occurs in a multiply-resonated, multiply-nodal, multi-temporal space.”

Although the trio last night conjured only one space—some sort of nature or stormy area—with their sound, they still operated, I think, in space rather than time. And of course any listener could argue that they heard multiple spaces. This is something that I have been calling vertical music, music that goes up and around in a space, rather than horizontal music, which operates along a continuum of time. The effect of vertical music is sometimes extremely boring, but it can be extremely riveting. Last night, it was astonishing. The musicians gave the audience a real experience, a home away from home.

My only qualm is that the production staff had to give Workman the “five-minutes left” signal. He smiled, understanding. But I imagined he wanted to go on forever.

Please don’t stop the music, I thought.

Both George Lewis and important bassist William Parker were in attendance Thursday evening.